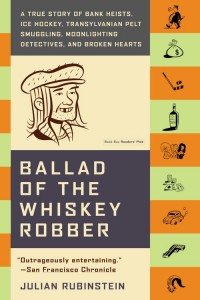

Ballad of the Whiskey Robber: A True Story of Bank Heists, Ice Hockey, Transylvanian Pelt Smuggling, Moonlighting Detectives, and Broken Hearts by Julian Rubinstein (2005, New York: Back Bay Books. Paperback. Pp. 352. $13.99. ISBN-10 0-316-01073-1)

Julian Rubinstein’s Ballad of the Whiskey Robber tells the true story of Attila Ambrus, a man with a taste for Johnny Walker Red who in the 1990’s went on a robbery spree in and around Budapest, Hungary. In six years, Ambrus carried out 29 robberies, hitting banks, post offices, and a few travel agencies along the way and raking in well over $800,000. His refusal to injure bank employees (and in some cases, charm the females with flowers), along with his hilarious taunting of the widely ridiculed police force chasing him, earned him broad popular support. In the anything-goes zeitgeist of post-communist Eastern Europe, where disdain for the government and its officials no longer needed to be hidden, Hungarians elevated the bandit to the status of folk hero in the mold of Robin Hood or John Dillinger.

And Ambrus did it all while playing goalie for UTE, one of the traditional powerhouse teams in the Hungarian professional hockey league; a team run, coincidently, by the country’s Interior Ministry–the agency in charge of the police.

THE CHICKY PANTHER

Late in the book and following Attila’s escape from jail, Rubinstein notes that Ambrus even made the pages of Sports Illustrated, and a quick search through that magazine’s sensational Vault turns up this “Scorecard” entry from August 16, 1999, which calls Ambrus

“… a hockey star … [and] one of the best goalies in his country’s top pro league.”

Not quite. Whether he was UTE’s back-up or whether he was their starter, Ambrus was never a hockey star. Few of the players in the league enjoyed any fame at all unless they were has-beens imported from the former Soviet Union. Either way, the role players like Ambrus weren’t even paid a living wage and many of them had other jobs.

But calling him a star is not nearly the exaggeration that calling him one of the best goalies is: In his first season as UTE’s starting goalie, Ambrus gave up 23 goals in one game, and 88 goals over a six-game stretch. The team was so awful they forfeited the remainder of their season. No one should have expected too much from a goalie who first did two years’ duty as an errant Zamboni driver living out of the janitor’s closet before he even landed the backup job.

However, playing hockey had been a childhood dream for him, and when Ambrus fled the Transylvania region of Romania for Hungary he did so seeking a better life and better opportunities to make something of himself in the world. Long before he began knocking over banks for big cash scores, Ambrus was on the phone calling the coach of UTE and asking for a tryout. Even though he was awful, the coaches and players were impressed with his superhuman stamina and his unequaled ability to put up with injury and abuse. During one practice, his own teammates were seeing who could hit Ambrus in the face with the puck the most times, breaking his nose in the process. But whatever abuse and disrespect they threw his way, Ambrus kept getting up and kept returning to the crease– old-school hockey qualities to say the least, and the kind that eventually earn at least a grudging respect from your peers.

However, playing hockey had been a childhood dream for him, and when Ambrus fled the Transylvania region of Romania for Hungary he did so seeking a better life and better opportunities to make something of himself in the world. Long before he began knocking over banks for big cash scores, Ambrus was on the phone calling the coach of UTE and asking for a tryout. Even though he was awful, the coaches and players were impressed with his superhuman stamina and his unequaled ability to put up with injury and abuse. During one practice, his own teammates were seeing who could hit Ambrus in the face with the puck the most times, breaking his nose in the process. But whatever abuse and disrespect they threw his way, Ambrus kept getting up and kept returning to the crease– old-school hockey qualities to say the least, and the kind that eventually earn at least a grudging respect from your peers.

Eventually, his teammates dubbed him the Chicky Panther– ‘Chicky’ referred to his hometown of Csikszereda in Transylvania, and ‘Panther’ referred to his quick, cat-like reflexes.

THE LONE WOLF

While his teammates called him the Chicky Panther, the frustrated, underpaid and understaffed Hungarian police force (including a police chief who learned how to be a cop by watching Columbo re-runs) referred to him as the Lone Wolf. Despite the fact that the thief was seen by countless witnesses prior to many of his heists getting drunk on whiskey in bars close to his targets, they couldn’t catch him to save their lives. What they didn’t know was that Ambrus was extraordinarily meticulous and detail-oriented about robbing banks, and some of the same qualities that earned him a spot on UTE– being in phenomenal physical shape and setting the bar so high for himself– contributed to his smashing success as a thief.

The police began referring to him as the Lone Wolf for an obvious reason– he was always alone. Not until he took on a full-time accomplice– one of his UTE teammates, in fact– did his luck begin to change, and it would be the capture of his accomplice during one robbery that would lead to his arrest.

ATTILA AMBRUS

Award-winning author Julian Rubinstein, who has written for Sports Illustrated, Rolling Stone, and Details, to name just a few, has built a taut, fast-paced, narrative that– wisely– reads like the best novel you’ve read in years even though this is an exhaustively researched work of non-fiction. The basic premise–back-up pro goalie robs banks to make ends meet–is already so good that Rubinstein himself admits he couldn’t believe his luck when he came across that very Sports Illustrated Scorecard entry mentioned earlier and found that there wasn’t a stampede of journalists rushing to Budapest to cover the story.

As outrageous as the premise is, and how full of comedic characters it is, Rubinstein paints a portrait of the Whiskey Robber himself sympathetically, almost as a tragic figure. As a criminal, Ambrus is very much a product of the political landscape transforming around him: his flight from Romania to Hungary occurs, historically speaking, as communism is crumbling: the Hungarian revolution, the Velvet revolution, the execution of the Romanian tyrant Ceauşescu, East Germany’s Die Wende and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, all set the stage for a folk hero whose brazen lifestyle satirizes those unstable and difficult times.

Yet Attila’s very status as a folk hero approaches the absurd, especially when a public deeply cynical about its burgeoning democratic government, begins envisioning him as a Robin-Hood figure. Robin Hood stole from the rich–OK, Attila did this–and gave it to the poor–Attila did not do this, although the public didn’t know that. Attila used the cash he stole to fund a lavish lifestyle replete with expensive cars and long nights of gambling and prostitutes, as well as taking the various women in his life on one extravagant, first class vacation after another.

A HOCKEY BOOK? NOT REALLY

Ballad is not what I or anyone would call a hockey book per se. But when hockey makes an appearance, it never disappoints. Among the many examples comes from a nationally televised game between UTE and arch rival FTC. In the second period a fight broke out that involved all the players, many of the fans, and lots of debris thrown through the air. At one point, a 12 year old kid needed to be taken out of the arena by ambulance, and afterwards the UTE coach tells the media:

“I’m not saying I wasn’t throwing anything, but I wasn’t the one who hit the boy.”

Sometimes, a non-fiction book like this can fail the reader in the illustrations section, but Ballad does the opposite: the book contains many of the pictures the reader would love to see, including one of the police line-ups with Attila in it; an almost beyond-belief picture from a press conference featuring Ambrus’ lawyer sitting next to a cardboard cut-out of his client; and perhaps the most telling of all: graffiti spray-painted on the wall of an apartment building by one of Attila’s many fans, illustrating how many robberies Ambrus got away with compared to how many times he’d been arrested by the Interior Ministry: 29-2.

To that end, the book is supported by a sensational web site that includes lots of great additional information, more photos, links to music by bands celebrating the Whiskey Robber, and even a link to the digital radio cabaret version of the book co-starring Eric Bogosian.

It’s altogether in line with the sublime lunacy of this story that the audiobook would be a cabaret version and not a straightforward reading: in the midst of the crime spree, a Budapest theater staged a cabaret about the Whiskey Robber that contributed to his fame, and on at least two occasions– and unknown to everyone in the house on those nights– the hero himself was watching from the front row.