A near-empty arena on a cold, Sunday night hosts an average men’s hockey league matchup. The skating leaves much to be desired, pucks fly well wide of the net, and every fourth pass ends up as an icing call. One devoted, young girlfriend takes photographs of her shoes when the momentum slows (frequently). The “Teal Blue” team faces the “Red” team. And it’s the highlight of my week.

I’m in goal for “Red”, and this night, I am filling in for our usual netminder who is sick. It’s great news because I grew up a goaltender and was taking a turn at defence (Aki Berg) for a year. It’s great news because our goalie is the equivalent of the NHL’s Vesa Toskala. The only equipment update I needed was a new mask. A simple, all-black mask.

Word that I was to play goal that night spread to a friend of mine who showed up to show his support – and embarass me. In the second period, a shot floats in from the point. It hits the post behind me and I glance quickly to my right for the rebound. I get there in time and the play goes the other way.

“Way to go, Darth! Nothing gets past the Evil Empire!” shouts my friend. I’m on team Red but no jersey fits me, so that night I’m wearing a black jersey and black mask. On an otherwise typical night in Canadian men’s league hockey, a character emerged and the three fans in attendance knew it.

Character goaltenders dominated my psyche growing up: Curtis Joseph’s “Cujo”, Eddie “The Eagle”, Felix “The Cat” Potvin. And they looked the part. Their characters became apparent because their disarming masks were simple and direct. A fan in the stands or a fan watching on television understood, from their distant vantage point, the impression those goalies (and their artists) meant to leave. Felix was quick like a cat, Belfour had eagle eyes, and Joseph was on that puck like a dog to a bone. Maybe it was the wrestling fan in me, reaching beyond reason for a template to place upon an actor in a play. But unlike baseball and basketball players, hockey players – and particularly goaltenders – wear protective helmets that obscure their faces. Who are these men?

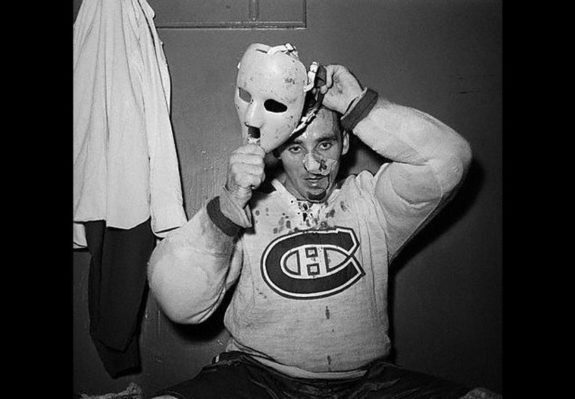

Before helmets were stylized, goalie masks represented the risk of playing the position and either proved or disproved one’s mental toughness. When Jacques Plante donned a mask for the first time, it was met with apprehension: “For most seasoned hockey men, the worst thing that could happen to a hockey player was the accusation that he was slowly becoming scared” (From Todd Denault’s Jacques Plante: The Man Who Changed The Face Of Hockey). Though years later, Gerry Cheevers of the Boston Bruins would paint stitches on his mask each time his “shield” saved him from injury. He was of course one of the “Big Bad Bruins”.

Today’s masks appear more like tapestries of a team’s history or one goaltender’s Facebook-ian “Likes”. Carey Price likes motorcycles: ”[The design] wasn’t really planned out that much,” explained Price. ”There were a few different ideas that the artist threw out; like the ace of spades, the Grim Reaper, and the chopper and I thought it looked pretty cool. I’ve always been a big fan of motorbikes, especially choppers, and I thought it looked really cool, so I threw it on there.” (TSN.ca). (The Undertaker “Likes” this). These ideas don’t translate to the fan unless CBC or TSN does a five minute special on why this mask is meaningful, and then it usually flops like a joke that has to be explained.

There are a few current masks that satisfy this writer’s thirst for Heroes and Heels. Nikolai Khabibulin, Stanley Cup champion with the 2004 Lightning, was dubbed “The Bulin Wall” and understandably had a brick wall painted on his lid. Jonas Hiller of the Anaheim Ducks also has a Darth Vader thing going on and while one Ducks TV commentator this year called it the worst mask in the league, I can appreciate the bold simplicity. Still, not much in the way of reflecting or creating an identity. It’s James Reimer of the Toronto Maple Leafs who leads the way in both literally assuming a super hero/alter ego and gesturing to his fans. Reimer’s “Optimus Reim”, a nod to the telelvision cartoon Transformers, is ideal. It plays on his name, popular culture, and speaks to his performance as a (so far, temporary) saviour for the team. Says Reimer: “”It’s a fun thing to do with the fans. If that’s what they know you by…” (theglobeandmail.com) and adds to that ““I have all of these things on my helmet for a reason” (ingoalmag.com).

Like my friend shouting “Use the force, Darth!”, these ideas tend to pop up naturally and can turn any typical game of hockey into a great performance.