Pavel Bure had already been regarded as an exciting young prospect in the Soviet Union when he landed in North America in September 1991. He headed to the NHL, accompanied by his father and brother, during a conflicting and changing time in world history. Communism was on the brink of collapsing in Bure’s homeland, and he was one of the first Russian nationals to make the move West for a chance to play in a different league. His final destination was Vancouver, who had drafted him in the 1989 NHL Entry Draft. It had taken two years for Bure to head to Vancouver to play for the Canucks, but he wanted to show a new audience why he had been on the NHL radar for just under a decade.

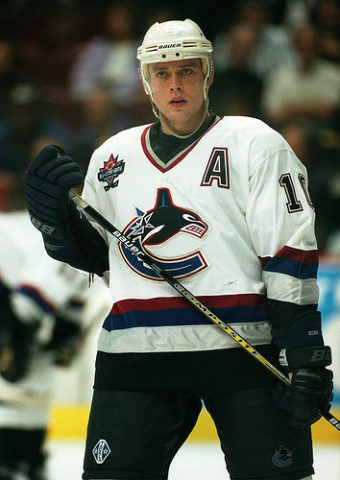

Bure’s rookie season blew the entire league away. His acceleration, skating, pace and clinical finishing earned him the nicknames “The Russian Rocket” and “the fastest Soviet creating since Sputnik.” He scored 60 points (34 goals, 26 assists) in the 1991-92 season and was awarded the Calder Memorial Trophy, the first Russian to win the award. Bure’s rookie season was an early sign that the best was yet to come. He scored 478 points in 428 games as a Canuck, hit the 100-point mark in two straight seasons, and guided his team to the 1994 Stanley Cup Final. Bure’s legacy on hockey and the Canucks had been made by the time he joined the Florida Panthers in 1998.

The hockey world considers Bure a trendsetter for Russians in the NHL thanks to his many goalscoring records and two Rocket Richard trophies, but political problems could have stopped him from making his effect on the game in the first place. He and many other Russian players initially headed to the NHL to add an international dimension, unaware that social tensions would affect them along the way.

Extortion Rumours Could Have Hindered Bure’s Career

An increasing number of Russian players began to follow Bure to the United States and Canada in the two seasons after he made his NHL debut, and there were campaigns to include more Russians in the league. One player who notably favoured a Russian player influx was forward Igor Larionov. Larionov, who joined Vancouver two years before Bure signed, was a well-respected player for the Soviet Union national team and mentored Bure on Vancouver’s top line. Despite their quick adaptation to a new style of hockey, Larionov and Bure were two of many Russian hockey players to be involved in an extortion scandal. Bure’s case was well-documented.

Reports suggested that Russian mafia officials were attempting to extort players because of large NHL contracts, with Bure’s name being mentioned. A rumour spread that the mafia had targeted Bure for several months and that Bure’s car had been blown up. Although Bure denied sending money to criminal organizations, he could not hide his friendship with prominent politician and businessman Anzor Kikalishvili. Kikalishvili was known to the FBI for suspected illegal activity, and he came across to American media as a bad influence in Bure’s life. Bure and Kikalishvili formed a close relationship and still maintain contact to this day, and Bure dismisses negative reports about Kikalishvili.

The FBI and RCMP investigated possible extortion cases, but no players were arrested or deported. The media attention could have damaged Bure’s reputation and morale, and he ensured that reports did not ruin his image in North America. Bure wanted to focus on playing hockey rather than answering to legal personnel, even though he was constantly asked about his supposed involvement with the mafia for many years after the fact.

Coming to the NHL Was a Personal Risk for Bure

Post-Cold War attitudes were still prevalent when Bure moved to Vancouver, and he felt anxious to come to a new country. He admitted that leaving the Soviet Union for Canada could have landed him in trouble, saying that there was “a very thin line” between migrating legally and being considered a defector. He did not want to go through the same struggles as Alexander Mogilny, who infamously defected to America against the government’s wishes and had to apply for political asylum. Thankfully, the Soviet government granted Bure the legal right to leave the country.

Russian hockey began to decline after Bure and many other compatriots moved to the NHL, but the NHL benefited greatly. Players such as Bure encouraged more Russians to play for American and Canadian teams as East-West political tensions settled, many of whom became Stanley Cup champions and Hockey Hall of Famers. Bure was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 2012, and the Vancouver Canucks retired his No. 10 jersey in 2013. Domestic issues could have forced Bure to make major changes to his playing career, but he grew through the struggles to cement his name in NHL folklore.