Until Jordan Greenway took to the ice for the US men’s ice hockey team in Pyeongchang, the program had never had an African-American player on its Olympic roster. It’s shocking it took so long, even with players such as Mike Grier, Seth Jones, Dustin Byfuglien and Kyle Okposo. But, what’s even more shocking is that it took more than 23 years after Canadian-born Willie O’Ree broke the NHL’s color barrier in 1958 for an African-American to break into the league.

His name isn’t heralded. It’s not one that is discussed every February during Black History Month. But it should be.

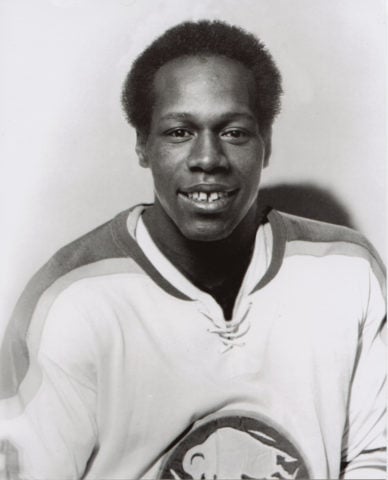

His name is Valmore James, but you can call him Val.

“I’m still trying to wrap my mind around [being a trailblazer],” he said. “To have my name in the same sentence with Jackie Robinson and Willie O’Ree, it’s like wow! It’s quite an honor, and I’d do it again in a second … When I was doing it at the time I never thought of it that way. I just wanted to be an NHL hockey player.”

Just a New York Kid

Born in Florida and raised on Long Island, James got a late start to his hockey career. He didn’t start skating until he was 13 years old and would lace up his skates late at night at Long Island Arena. In the beginning, it was James, a wooden chair, and his Doberman.

“I was fortunate my dad was running the rink so that I could get ice time after everyone was done with it,” said James with a smile. “[My Doberman would] always submarine me. He was my best friend and my worst enemy on the ice.”

Growing up and playing hockey on Long Island, James was like any other player on the team—he was a hockey player. But, when he left home he was faced with the stark reality that he was not just a hockey player.

“He made sure to point me out,” said James when discussing his experience at a tournament in Michigan as a young teenager. “He was talking to me until he came down to the glass and said what he needed to say to me. It just crushed me. I was completely out of it for a period, period and a half, before I actually came back to normal.

“I think I was a little bit shocked. I was probably prepared for it a little bit, but not to come that quickly. I figured something that would happen when I got a little older. I didn’t know that when you’re dealing with older people, that they have their set ways of thinking that that’s what would happen.”

Breaking Through

An enforcer, James was drafted by the Detroit Red Wings in the 16th round (184th overall) in 1977. In 1981, the then-Rochester American received “the call” and made history as he skated in his first NHL game.

“It was unbelievable because that’s what I was working for all these years – to get to the NHL,” James said with a smile. “Being the first African-American in the NHL didn’t cross my mind. Just being able to play in the actual NHL was the only thing that I could think of at that point in time. I was on top of the world you know. I just loved it.”

While his first NHL game with the Buffalo Sabres was a moment he’ll never forget, the racism he faced as a young man followed him throughout his minor league and NHL career.

“We ended up going to Boston later that week [after his first NHL game], and that’s when all the altercations started to happen after the game,” James recalled. “They kind of shook the bus up a little bit, like they wanted to turn it over. They spiderwebbed the windshield with beer bottles. It was one of those hectic times. I was more concerned for the players that were with me because I knew if something happened they’d be right there and someone would have gotten hurt for sure.”

“I’m not blaming the whole city of Boston—just those few individuals that felt the need to show their ignorance.”

Not Just an Enforcer

A feared enforcer on the ice, James played a total of 11 NHL games for the Sabres and Toronto Maple Leafs. In those games, he notched 30 penalty minutes and three fights—including one against Terry O’Reilly. But, while he didn’t score an NHL goal, James scored one of the biggest goals in Rochester Americans history: the goal that clinched the Calder Cup in 1983.

“That was incredible,” James said with a grin. “Just from the practices in the big leagues, instinct took over. It’s an automatic shot and that’s what I did. I saw the corner before I even took the shot and just shot at it as soon as I got the puck and it went in. But, I didn’t look at it as a game-winning goal at the time. I didn’t even realize it until somebody told me.”

Still a fan favorite in Rochester, James retired after the 1987-88 season—and stepped away from the game.

“It took me 10 years to get over all the racial slurs I had [heard] before I even watched a hockey game [again],” James said. “[It was] another seven before I could even complete a game … It was a hard time because you know all those memories came flooding back.”

Leaving a Legacy

When James broke into the league there had only been a handful of black NHL players. Since then, the number of black players—and black American hockey players—has grown.

“I’m black. I’m a hockey player. I can’t get away from that,” said James, who published an autobiography in 2015. “I feel I have opened a few doors for guys that might not have gotten that chance later on in their careers. So to be able to do something like that for someone, whether it be my race or someone else’s race, it’s just a nice thing to do.”

Unfortunately, work still needs to be done, as was seen recently in Chicago where the Washington Capitals Devante Smith-Pelley faced racial taunts from Blackhawks fans. But James knows he left a legacy in hockey that can only be built upon.

“It’s nice to see finally there is a color in the sport besides white, and it’s not that it’s a bad thing,” James noted. “It’s like having a fruit salad with just oranges in it – What good is that? All the grapes, the melons, the pears and all of that in it and the strawberries. Now you’ve got color. You’ve got texture and it’s much better.”