The San Jose Sharks have been rolling six defensemen in each game. But that doesn’t mean all six will play equally. Peter DeBoer shows confidence in five defensemen, not six. This is especially apparent in the third period, where appearances by a sixth defensemen are about as rare as snow in San Jose.

The five defensemen DeBoer rolls are: Marc-Edouard Vlasic, usually paired with Justin Braun; Brent Burns usually paired with Paul Martin; and Brenden Dillon. Dillon is paired, at least to start the game, with the sixth defenseman, usually Matt Tennyson or (less often) Mirco Mueller.

All About Trust

In an earlier article, I covered the lack of trust DeBoer has shown in Tennyson. There are games where Tennyson has deserved his benching, most notably a game against the Blackhawks where he was just plain bad. But those seem to be more the exception –DeBoer benches his sixth defenseman largely independent of their quality of play. For example, against Anaheim on Friday night, Tennyson played quite well for two periods. Even so, he was relegated to the bench for the first 13 minutes of the third period. This despite an injury earlier in that period which had taken Vlasic out of the rotation. Tennyson was off the ice for around 45 minutes, then asked to jump in for a shift in the closing stretch of a one goal game. Not easy to do that well.

Ice Time Considerations

The five defensemen approach is only modestly applied in the first two periods, when the sixth defenseman often gets a reasonable share of shifts. But that comes to a halt in the third period. Can the Sharks succeed with a ‘five defenseman’ strategy, where they play essentially the entire third period? Two factors jump out. One concern is excessive ice time. There are nominally 120 minutes of ice time for defensemen per game, divided up among six players. Playing a sixth defenseman limited minutes means there is around 110 minutes to be divided up among five players, an average of 22 minutes per player per night. Last season, 54 NHL defensemen had an average of 22 or more minutes of ice time per game. 82 defensemen exceeded 21 minutes per game. These are not huge time-on-ice numbers for a defenseman.

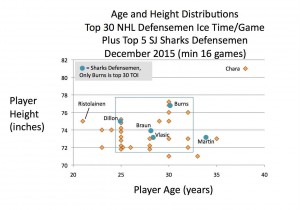

I have developed charts looking at height and age for the top 30 forwards in ice time. For defensemen, the chart skews a bit. The average for defensemen pulling big minutes is 1 year older and an inch taller than it is for forwards. 28 years old and 6’2” are the averages for defensemen. The Sharks’ Justin Braun is dead center on that midpoint. I’ve included the Sharks five defensemen in the graphic.

Only Brent Burns is in the top 30 in ice time per game, though Marc-Edouard Vlasic is 31st. Only Paul Martin is outside the grouping likely to handle major minutes. But Martin is not handling major minutes, he is 90th in the NHL in ice time among defensemen. The question of whether the Sharks defensemen can handle the added ice time is pretty clear. With the exception of Paul Martin, they are well inside the age/height sweet spot. They should be able to handle the increased load.

Defensive Chemistry

The second item is more problematic. Good defensive partners combine two things: good skills and the ability to work well together. When rolling five defensemen, Peter DeBoer juggles his defense pairs for the entire period. Not all pairings work together equally well.

It is necessary for any hockey player to be able to play effectively with any of his teammates. Teams develop systems so that the responsibility for a player to be in a spot is independent of which player is on the ice. Still, players have individual tendencies, styles and preferences. Knowing who your partner is and how to play most effectively with them is something that usually takes time. Players talk about ‘not thinking’ when they have good chemistry with their partner. They just know, which optimizes reaction time.

When partners get juggled, players need to be a bit more aware of which player they are out there with. That extra mental demand can slow things down just enough to create problems. Subtle things like needing to remember if a player is on the ice with a left-handed partner or a right-handed partner becomes meaningful if it creates moments of hesitation.

Some pairings have limited chemistry. Brenden Dillon and Brent Burns are a match made somewhere other than heaven. They played poorly together last season. Burns was paired with Martin this year and the two have played effectively together. Still, when Martin went down early in the season for three games, DeBoer put Burns and Dillon together again. It did not go well.

In Friday’s loss against key rival Anaheim, it was Burns and Dillon on the ice together for the game’s lone goal, occurring in the third period. Perhaps just as noteworthy, the Sharks played most of the third period in their own defensive zone. The defense struggled to clear the puck making any up-ice transition game almost non-existent. One can’t prove that this problem was, at least in part, a result of juggling of defensive pairs. But it belongs on the suspect list (Vlasic’s absence for a good part of the period was also an issue in this specific game). Anaheim’s speed overwhelmed the Sharks in that period, something that had not happened in the first two periods when the starting defense pairings were kept together during 5-on-5 play. One suspect can be eliminated, though. The Sharks were not tired for this Friday night game, having last played on Tuesday.

Suboptimal Impact

Peter DeBoer’s five-person defensive core strategy is workable from a player energy perspective. The extra minutes should not be an issue. What is more problematic is the constant juggling of pairings. Among five players, there are ten different potential pairing combinations. The idea that a player is equally well-adapted to each of the other players is wrong. Chemistry between players exists. Players are interchangeable, but sometimes effectiveness is compromised. Some of those ten combinations are bound to be substandard compared to others. Paul Martin seems to bring out the best in Brent Burns, Brenden Dillon does not.

It is difficult to prove cause and effect since there are many factors involved, but the evidence clearly says DeBoer’s approach has not had the desired net impact.

Through 25 games, the Sharks, in the first period, are outscoring their opponents 21-18. They are also getting it done in the second period, outscoring opponents 26-21. The third period, though, they have been outscored 25-17. Only four teams have a worse third period goal differential than the Sharks minus-8 and only three teams have fewer third period goals.

In the last ten games (through the Anaheim game on Friday night), the Sharks have won seven, including a sweep of a six game road trip where the Sharks rarely played their sixth defenseman for more than a shift or two in the final period. Over those ten games, the Sharks have outscored opponents in the first two periods by a total of 18-13. They have been outscored in the third period 11-7. Exclude the terrific comeback win versus Columbus, and the Sharks have been outscored in the third period 10-3. The Columbus game is the only game in the last ten where one could even potentially cite the ‘five defenseman’ strategy having a positive effect on the outcome. The Sharks have been outscored in the third period in seven of the last ten games, while outscoring the opponent only twice.

The numbers make a clear case, the Sharks success over the last ten games has been due to success in the first two periods and in overtime, (where they are 2-0). The third period, has, a lot more often than not, been a problem. Measured by results in several different ways, the ‘five defenseman’ strategy is not working.