Every year renews the age-old debate as to whether or not the Georges Vezina Trophy and the other major NHL awards should be renamed. The argument usually goes that the names of bygone hockey legends (often men such as Frank Calder and Conn Smythe who laid the foundations for hockey becoming a major sport in North America) have faded from the memory of today’s players and fans. We should, the argument concludes, rename the NHL’s annual honours after more recent stars such as Gordie Howe, Bobby Orr, and Wayne Gretzky.

I don’t believe in tradition for tradition’s sake, so I’m not staunchly opposed to renaming some awards. I am, however, against renaming or retiring the Vezina Trophy because it’s namesake, Georges Vezina (1887-1926), is simply too great of a figure from hockey’s early history to relinquish. If the memory of this legendary goalie has receded from the collective psyche of hockey fans, then it’s our fault for not appreciating his indisputable greatness.

Here’s a brief list of reasons why Vezina is worth remembering.

1. Georges Vezina Began that Whole “Montreal Canadiens Thing” (And May Have Inspired the Film Citizen Kane)

Georges Vezina did not found the Montreal Canadiens, but he did establish their reputation as the winningest team in Stanley Cup history by helping the Habs (then part of the National Hockey Association) clinch their first berth in the Stanley Cup Finals in 1916. Vezina and the Habs won the Cup that year and thereby clinched the first major accolade for an organization that would become the most decorated franchise in NHL history. Incidentally, Vezina also won the Cup in 1924 when the Habs were part of the NHL, so he was an integral part of Montreal’s first championships in both their NHA and NHL history.

To win their first Stanley Cup, the Canadiens had to defeat the Portland Rosebuds. Some film critics claim that Herman Mankiewicz drew upon the loss of his own beloved bicycle as the basis for Charles Foster Kane’s preoccupation with the childhood sled called “rosebud.” However, it’s long been my opinion that Vezina’s defeat of the Portland Rosebuds provided the actual basis for Mankiewicz’s sense of irremediable loss that haunted his own life and that of the fictional Kane. The memory of the Habs edging the Rosebuds 2-1 in the fifth game of the best-of-five Stanley Cup Finals of 1916 would be enough to madden any diehard fan of the Portland team, which folded a mere two years after the Canadiens cruelly snatched the Cup from their grasp.

For a modern example of how a playoff collapse can become a source of lifelong torment, consider Joffrey Lupul who, in relation to the Toronto Maple Leafs’ overtime loss to the Boston Bruins in the 2013 NHL Playoffs, tweeted,”That hockey game will haunt me until the day I die.”

2. Georges Vezina’s Silence Was Legendary

Vezina’s fame was based on his ability to stop pucks as well as his aversion to talking with reporters during his professional career. To avoid contact with the media, he allowed the team’s management to speak for him. Leo Dandurand, an American owner and coach of the Habs during Vezina’s career, claimed that Vezina’s silence stemmed from the language barrier between him and the Anglophone reporters. In actuality, Vezina could speak broken English as well as many of today’s players.

Dandarund didn’t just rationalize Vezina’s actions but used his position as spokesperson to mythologize his mysterious netminder. He told reporters that Vezina was “a real French-Canadian,” which meant that he spoke no English and fathered 22 children (including three sets of triplets) in nine years. Apparently, at that time, English Canadians thought that Quebec denied its residents fundamental rights of Canadian citizenship until they fathered a sufficient number of children (including at least two instances of multiple births) within a certain number of years.

Vezina’s example offers a model for other shy NHLers. Think of how Phil Kessel might have benefited from avoiding the glaring lights of the Toronto media by simply having Dave Nonis explain to reporters (such as those annoyed when the Leafs sniper snubbed reporters ahead of the 2013 NHL playoffs) that Kessel’s Wisconsin dialect made him incapable of responding to questions, and that Kessel, as a “real Madisonian,” spent his off hours making clocks out of cheddar cheese. There’s one PR problem solved and a new hockey legend born!

3. Georges Vezina Invented the Shutout

Vezina may have been quiet in the dressing room, but he made his presence known on the score sheet. He recorded both the first assist by a goaltender and the first shutout in NHL history. Keep in mind that high-scoring games were the norm during his career. This era set records for the most goals scored by a team against an opponent in one game (Montreal massacred Quebec with a 16-3 win in 1920), and the most goals scored (by both teams combined) in a single game (Montreal’s 14-7 victory over Toronto in 1920–the year of high scores!). In the game against Toronto, Montreal forward “Newsy” Lalonde also set an NHL record by scoring six goals.

When Vezina recorded the first NHL shutout, he did so as part of a 9-0 Montreal victory over the Toronto Blueshirts on February 18, 1918. That’s right: the Vezina-backed Canadiens humiliated Toronto that night by refusing to give up a goal in order to offer the badly beaten Blueshirts a modicum of respect.

By recording the first NHL shutout, Vezina started the shutout trend among goaltenders that would make goalies the most hated figures in hockey according to fans, reporters and league executives who feel that the sport’s entertainment value stems solely from the quantity of goals scored rather than the quality of saves made.

4. Georges Vezina’s Unique (Although Somewhat Inappropriate) Epithet

Vezina’s unflappable composure earned him the epithet “The Chicoutimi Cucumber.” I’m using “epithet” instead of “nickname” because a nickname is usually something used in place of a person’s first name (e.g. referring to Vezina’s contemporary Edouard Lalonde as “Newsy”). Vezina’s honorific name is more akin to phrases associated with great figures in history (e.g. referring to Elizabeth I as “The Virgin Queen”). It’s safe to say that few people in the Habs dressing room circa 1920 would say, “How are you today, Chicoutimi Cucumber?”

While that nickname is certainly unique, it isn’t particularly apt given that Vezina was 5-foor-6. I suppose the goaltender would have objected to an apt, but also insulting, nickname such as Georges “Gherkin” Vezina. This alias has the benefit of also alluding to the procedure of pickling animal hides in the process of tanning, which is an occupation that Vezina practiced during the offseason in his tannery located in Chicoutimi.

Of course, Vezina’s other accepted epithet also works well. The reserved goaltender liked to sit quietly in his corner of the Canadiens’ dressing room and read the newspaper while smoking a pipe. Since “Newsy” was already taken by Vezina’s teammate, and “Popeye” wouldn’t make his first appearance in comic strips until 1929, Vezina was given the epithet “The Silent Habitant” to describe his reticent behaviour. Thus in terms of celebrity as well as demeanour, Vezina was the George Harrison (a.k.a. “the quiet Beatle”) of his day.

5. Georges Vezina Put His Career on the Line for Canada

Despite Vezina’s stature and chain-piping habit, he was considered an elite athlete in his day. So much so that he was chosen to play a special exhibition game. In 1917, the Canadiens played against a team comprising soldiers in order to raise money to help Canada manage costs associated with the First World War.

The teams agreed that Vezina would play goal for the soldiers in order to even things up. That’s right: making the pint-sized puck-stopper play against his own team was considered enough to make a group of amateurs competitive against the Canadiens. Sure, the Habs hadn’t yet become the legendary franchise that they are today, but they were still an elite team by comparison in 1917.

It’s worth noting that Vezina’s participation in this event was a bit risky. The First World War became increasingly unpopular in Quebec as the protracted conflict continued. The reluctance of Quebec residents to enlist reached a boiling point when the Canadian government’s policy of conscription resulted in the Easter riots of 1918. To pacify these militant mobs, Prime Minister Robert Borden dispatched troops to restore peace and order in Quebec – at least long enough to press some of those rioters into active military service.

Even before these events, the war was seen by many residents of Quebec as antithetical to French-Canadian nationalism. Given this political climate, Vezina and his teammates risked incurring the ire of nationalistes by participating in an event to bolster Canada’s war effort. By fraternizing with troops-turned-teammates for that exhibition game, Vezina particularly risked losing his reputation and career as Montreal’s premier goaltender by backing soldiers that would later be tasked with suppressing the Easter riots.

6. Georges Vezina Redefined the Word “Stamina”

It’s safe to say (without any hyperbole) that if Skynet had modeled its cyborg assassins after Georges Vezina instead of Arnold Schwarzenegger, Sarah Connor would have been terminated quicker than you can say “I’ll be back.”

Among Vezina’s most impressive accomplishments is the streak of playing 328 consecutive regular season and 39 straight playoff games for the Habs. Here’s another way to put that streak: from 1911 to 1925, Vezina didn’t miss a single game unless he was barred from playing. He was prevented from playing games twice in his career.

The first time occurred when the outbreak of the “Spanish Flu,” which afflicted so many hockey players that the NHL decided to cancel the Stanley Cup Finals in 1919. Unlike the cancellation of the 2004-05 playoffs due to discord between the NHL and NHLPA, the 1919 cancellation was entirely justifiable as the virus, which ravaged numerous countries, claimed the lives of Habs defenceman Joe Hall and Habs owner George Kennedy among many other victims. So, aside from a global pandemic, Vezina suited up for every game played by the Habs during his career.

He even suited up for that final game in which he was physically removed from his crease. On 28 November 1925, Vezina decided to play despite having a high fever. Some reporters claimed that it was 102 degrees Fahrenheit while others claim it was as high as 105. (The second number might have actually been a reporter’s estimation of the number of children that Vezina had fathered by that time.)

While his strong play kept the Pittsburgh Pirates from scoring in the first period, Vezina’s health was visibly deteriorating. Shortly after entering the dressing room with blood spattering from his mouth, Vezina collapsed. Undeterred by the rupturing of his lungs and lapse in consciousness, Vezina started the second period but soon collapsed in his crease. At this point, the Habs decided that he was unfit to play or at least, for once, physically unabe to prevent them from pulling him from the net. “Pulling” is an exaggeration as the gaunt goaltender had to be carried away from his net that night.

While the official diagnosis of tuberculosis came shortly after his collapse, the organization had noticed Vezina’s dramatic loss of weight and sickly appearance during training camp in 1925. His stellar performance as the team geared up for the 1925-26 season kept the organization from intervening for the sake of his well-being at that time. Based on this information, it’s safe to say that Vezina had played through the effects of tuberculosis for a while before his collapse.

7. Georges Vezina’s Extenuating Circumstances

Vezina’s career goals-against average was 3.49, which means he is outside the NHL’s all-time top 100 goalies in terms of GAA.

Some defend Vezina’s record by noting that, for half of his career, goalies were assessed minor penalties if they left their feet to stop pucks. This rule would be abolished ahead of the 1917-18 season after the league found it nearly impossible to determine if a goaltender lost his balance when he fell and made a save, or if he intentionally threw himself in the puck’s path. So for those of you who bemoan the practice of diving in the NHL, keep in mind that this form of embellishment is older than the league itself.

Another rule that put Vezina at a disadvantage prevented goaltenders from passing the puck forward. This rule was changed ahead of the 1921-22 season (toward the end of Vezina’s career) to allow goalies to pass the puck toward their own blueline.

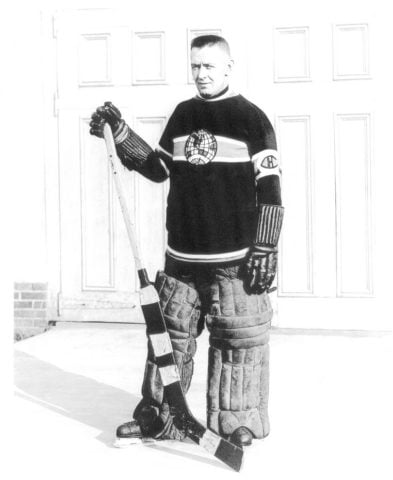

Those facts explain some but not the whole story. To put things in context, remember that Vezina was a pipe-smoking, tubercular goaltender whose 5-foot-six stature barely filled the net. Of recent NHL goalies, the shortest stand 5-foor-10 (a three-way tie among the St. Louis Blues’ Jaroslav Halak, the Buffalo Sabres’ Jhonas Enroth, and the Dallas Stars’ Richard Bachman).

Vezina’s humble stature explains why he appeared to be wielding a claymore-sized cudgel when posing with his goalie stick.

So, whether you call him “The Cucumber” or “The Gherkin,” let’s give Vezina credit and preserve him in our memory as the toughest little guy ever to curate the crease in the NHL.

This article was originally published in June, 2013.