It’s not an untold story, but it is certainly a rarely told and uncomfortably unknown piece of hockey history.

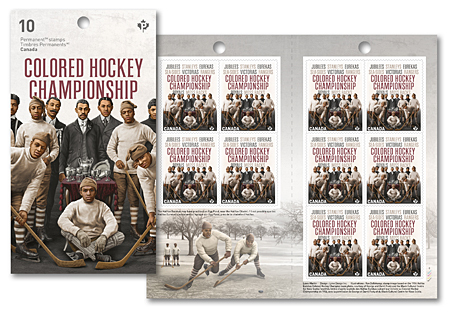

In January 2020, Canada Post released a special stamp and first day cover featuring what is undoubtedly hockey’s greatest secret. The stamp features teams and artwork of players from the Colored Hockey League.

Between 1895 and the early 1930s, all-Black ice hockey teams in the Maritimes thrilled mixed audiences and news reporters alike as they challenged each other to exciting matches and vied for the ultimate prize — the Colored Hockey Championship.

Created as a means of drawing more men to church and strengthening their religious path, all-Black hockey also served to dispel myths about Black people’s abilities. With their fast-paced, physical games and down-to-the-ice style of goaltending, the players made real contributions to the game. While winning on the ice was a moment to celebrate, the greater triumph was the pride experienced by Black communities across the region.

“I grew up watching hockey without knowing the legacy of these teams,” said Craig Smith, President of the Black Cultural Centre for Nova Scotia. “Telling this important story will broaden the public’s understanding of the contributions of the African-Canadian community in the Maritimes to our national winter sport.”

Most Canadians don’t know about this intersection in the history of Canadian culture, but it is possibly the greatest Canadian story, and one of the world’s greatest sports stories, rarely told.

Hockey fans may know of the Montreal Wanderers, the Ottawa Silver Seven, the Winnipeg Victorias, the Vancouver Millionaires, the Seattle Metropolitans, and some of the teams from the early years of the Stanley Cup. But very few have ever heard of the Africville Sea-Sides, the Halifax Eurekas and the Halifax Stanley, who were the original teams that formed Canada’s first organized hockey league, the Colored Hockey League.

As our cultural ignorance evolved, it seemed odd for fans to see a Black hockey player. Willie O’Ree broke the NHL’s color barrier in 1958 with the Boston Bruins. But it wasn’t until the 1974-75 season that 19-year-old rookie Mike Marson would become the league’s second Black player, as he made the expansion Washington Capitals.

If only the average hockey fan knew the history of the game and the role that Black players had played as the game evolved early in the 20th Century.

While sports played an important cultural role in the history of Canada and the U.S., there was a big difference. In the U.S., you would never see multi-racial sandlot baseball games being played. In Canada, however, once a kid put a pair of skates on and went out on the pond, it rarely mattered what color he was.

More than a century ago, hockey played a huge role in Canadian Black culture on the east coast. The Black leaders of the day recognized it, and they used hockey as a vehicle for advancement.

Colored Hockey League Pre-Dates NHL, Negro Baseball League

The Colored Hockey League has perhaps the most intriguing history of any sports league in North American history. It was formed in 1895, pre-dating the formation of the NHL by more than 20 years. The league also pre-dates the Negro Baseball League in the United States. What makes it interesting is that the league was actually formed by the Baptist Church. The mandate of the league was to use hockey as a way of advancing young Black men to a level equal to their white brethren through a game that would instill the qualities of leadership, community, organization, pride, teamwork and determination.

Henry Sylvester Williams and Brother James Borden were two of the visionaries who guided the formation of the league. They were both church men who saw the social and political importance of using hockey to encourage advancement of Black men. They also saw it as a way to attract young men and families to churches that were suffering from stagnating attendance.

Williams’ Cornwallis Baptist Church in Halifax would form two teams — the Halifax Stanley and the Halifax Eurekas. Across the harbour, Borden would form the Dartmouth Jubilees from his Lake Baptist Church. The league was operated by the church, making it unique in North American history. The official rule book was the Bible.

The first-ever Colored Hockey League game was played on Feb. 27, 1895 at the Dartmouth Curling Rink. The Eurekas and the Jubilees skated to a 1-1 tie.

The league received press and coverage from the Acadian Recorder, which was one of three Halifax newspapers of the day, and it was Baptist-owned. The Recorder reported that the game featured a much more physical style of play than the more gentlemanly white teams would play, as the players would partake in “body-checking” and “cross counters” (short punches). The Recorder also reported through the first season that the ladies would turn out in full force for the games, cheering loudly.

There were no nets and curling stones were used as posts. The star of the Jubilees was their goalie, Henry “Braces” Franklyn. An ice cutter by trade, Franklyn revolutionized his position as he was the first goalie who reportedly went down on the ice to make saves in the game’s history. Franklyn’s butterfly style was eventually made popular by goalies like Glenn Hall and Patrick Roy.

Another innovation of the Colored Hockey League was the slap shot. It may have been made famous by Bernie “Boom Boom” Geoffrion and Bobby Hull, but it was Colored Hockey League star Eddie Martin who invented it.

The Stanley would win the first championship, while the Eurekas would win the next five.

In the early 1900s, the league grew. The Africville Sea-Sides, the Truro Victorias, the Charlottetown West End Rangers, the Amherst Royals, and the Hammond Plains Moss Backs joined the original three teams. The Colored Hockey Championship was organized as a challenge cup system.

The season was short, usually running from late January to early March, as artificial ice was not available in the Maritimes. The league also had to take whatever ice times were available, as they had to work around the schedules of the white teams and leagues.

Regardless, attendance was strong. Some playoff and championship games drew more than 1,000 spectators. The caliber of play was considered by many to be on par with that scene in the best white leagues.

Politics Interfered With CHL

Unfortunately, as the league was thriving, politics and racism became an obstacle. Expanded rail service into the port of Halifax led to the annexation of land from many families in Africville, the Black community in Halifax. A five-year legal battle ensued, and many rink owners refused to rent ice time to the league or any of its teams. Under pressure from municipal and provincial officials, the local newspapers stopped covering the league.

The 1905-06 season did not start until later in March, when the natural ice was melting and virtually unplayable. The league, after that season, moved back onto the ponds and lakes to be played outdoors.

There are no newspaper accounts of any Colored Hockey League play from 1911-20, but in 1921, the league resurfaced in the public eye. Three teams, the Victorias, the Sea-Sides and the Halifax All-Stars, formed a three-team league. The league was not as strong as it was in its prime.

In the 1930s, the league would fade away. Many Black families left the economical repression they suffered in Nova Scotia for the greener pastures of Boston. Although new teams like the Africville Brown Bombers, Halifax Diamonds, Halifax Wizards, New Glasgow Speed Boys and Truro Shieks would emerge, the league was gone and forgotten by the time World War II had begun.

There is very little history on this hockey league, which is why Canada Post’s 2020 Colored Hockey League stamp series is so significant.

In 2004, hockey researchers Darril George Fosty released a book entitled “Black Ice: The Lost History of the Colored Hockey League of the Maritimes, 1895 to 1925.”

The Hockey Hall of Fame also has an exhibit that includes information on the Colored Hockey League. “The Changing Face of Hockey – Diversity in Our Game” is a permanent exhibit that brings to light the challenges faced by marginalized people across North America in their struggle for social equality and acceptance in the great game of hockey.

The display pays homage to the pioneers who confronted discrimination from the hockey world through their perseverance, talent, and courage. They have enriched the cultural landscape of hockey and established a tangible forum in which to fight prejudices still faced by many, both in hockey and in life.

The display makes its permanent home within the Hometown Hockey Zone.

To date, there have been nearly 100 Black players to lace up and play in the NHL. Some, like O’Ree, have been pioneers. Some, like Grant Fuhr, have been Stanley Cup champions. Some, like Jarome Iginla, have become superstars.

They have all become household names to hockey fans.

It’s time the players and teams from the Colored Hockey League became widely known in the hockey world as well.