The hockey world turned on its head Wednesday afternoon as the first big pieces began to move prior to the beginning of the 2016 free-agency period. Nashville and Montreal swapped all-star defensemen P.K. Subban and Shea Weber, and Edmonton and New Jersey swapped former top five picks, Taylor Hall and Adam Larsson – both within moments of one another.

Hockey fans, and even fellow players, reacted in shock as the news broke of the afternoon’s trades. The chatter wasn’t just reaction to the players being moved, but mere astonishment of elite-level talent moving from one team to another.

Compared to the MLB, NFL and NBA, high-profile, free-agent signings and trades are a rarity in the NHL.

The NHL’s largest free-agent contracts over the past five years where a player moved from his original team were those of Zach Parise and Ryan Suter, who signed identical 13-year deals with Minnesota prior to the 2012-13 season, each at $7.5 million per year. Compare this to the MLB, where last offseason only three of the 20 largest offseason deals were signed by players who stayed with the same team.

Why don’t the NHL elites move teams as often as their professional counterparts? There is no single factor to point at to explain this phenomenon – or lack thereof in this case. However, a consistent concern across other professional leagues is players not being able to replicate the same level of production when moving to a new team. Every general manager’s worst nightmare is to have a similar situation as the LA Angels in the MLB, who signed Albert Pujols to a $250 million contract in 2012, only to see his batting numbers decline drastically.

For every lucrative free-agent contract and superstar-packed trade in professional sports that pans out, there is sure to be one that failed miserably. Should NHL teams be more willing to sign and trade for star players, or are these moves a catastrophe waiting to happen?

What the Data Says

In the middle of Wednesday’s madness was another important piece of news: Steven Stamkos had decided to stay with the Tampa Bay Lightning. Stamkos put to bed the rumors swirling of him possibly leaving to join either Toronto, Detroit or Buffalo. If history tells us anything, we shouldn’t be surprised Stamkos opted to stay put.

For the 2015 free-agency period, 65 percent of players who signed a contract in the NBA moved to a new team. In the NHL, 42 percent of players signed a contract with a new team. The majority of players in the NHL are staying with their current team, let alone signing large contracts to head elsewhere.

Since 2011, 81 skaters have signed a contract in free agency to move to a new team in excess of $2.5 million a season. When the average salary is doubled to $5 million, the number of skaters drops to just 21 over the past five years.

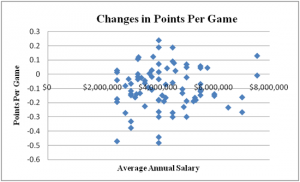

For the players who did cash in during free agency, the size of their contract has had little to no effect on their production. The scatter plot shows each player’s change in points per game based on their average salary. Points per game were used to control for differing amount of games played over the course of the five-year period, and injuries. The change is simply how many points per game the player averages now compared to before they signed their new contract.

What this chart shows is there almost no correlation between the size of a player’s contract and their change in production. While this is promising news for advocates of lucrative contracts, it doesn’t paint the entire picture.

Since the 2006-07 NHL season, a total of 1,128 NHL players have moved teams at least once. On average, players who do move from their original teams have gone on to play for two more.

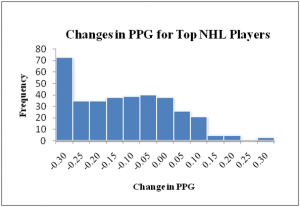

To get a clearer picture of how the NHL’s top players were being affected by this movement, this group was broken down into the top 25 percent in ice time before being moved by both forwards and defensemen. The intuition behind this is simple; more often than not the best players are the ones who play the most.

There is a fairly noticeable skew in the data – more players are falling on the negative side o f the graph. The top 25 percent of forwards and defensemen by ice time, on average, are seeing their points per game decrease by -0.16, or about 13 points for an 82-game season.

f the graph. The top 25 percent of forwards and defensemen by ice time, on average, are seeing their points per game decrease by -0.16, or about 13 points for an 82-game season.

What might explain this negative trend? The strongest indicators point towards changes in time-on-ice per game, and shots on goal per game. Using regression analysis with these two variables shows about 60 percent of the variation in points per game can be explained by the two. Below is the regression equation that was computed:

Change in Points/Gm = -.06 + .029Change in TOI/Gm + .155 Change in Shots/Gm

There are still other factors that may be causing players to trend towards a decrease in points with their new team. Some of these may include psychological effects of moving to a new team, chemistry with new linemates, changes in expectations and on. However, among the reasons doesn’t seem to be age.

It could be easy to imagine star players who are being traded late in their career to chase Cups are skewing the data, but in fact there is not much of a correlation between the two.

The scatter plot shows a slight negative trend – the older the age the greater decrease in points per game. The correlation exists, but isn’t very strong.

What We Learned

There are many great NHL players who have signed a large contract, or been in a blockbuster trade, and continued to have a successful career. Some notable players such as Brent Burns, James Neal and Ryan O’ Reillly have all been traded and gone on to improve their numbers drastically for their new team.

Despite these success stories, the majority of elite NHL talent moving from one team to another results in a drop in production. Much of this change in production can be measured by changes in ice time and shots, but the rest is difficult to quantify and leaves some questions unanswered.

NHL teams are sure to open up their checkbooks and shell out millions to players this free agency, but before they do they should think twice.

All data in this article is courtesy of espn.go.com, hockeyabstract.com and hockey-reference.com.