The “New NHL” is not so new anymore.

After the player lockout in 2004-05 saw an entire season canceled, the NHL’s front office made an effort to change the game on many levels. This was done to bring the fans back and maybe even pick up some new fans along the way. This included the expulsion of the two-line pass, restrictions of goaltenders playing pucks behind the net and even introduced the shootout to regular season games.

It also included zero tolerance for hooking, holding, tripping, slashing, cross-checking and most importantly, interference.

The enforcement of existing rules made the power-play opportunities skyrocket league-wide. The season before the lockout, there were 10,427 power-play opportunities in the league. In 2005-06, that number rose to 14,390 opportunities (3,963 more chances for teams with the man-advantage).

All rule changes, including cutting down the size of goaltending equipment, were made in effort to promote goal-scoring and shy away from the stingy defensive play that took over the game in the 1990s.

Initially, the rule changes worked as there was almost one more goal scored per NHL game in 2005-06 (0.91).

This was mostly credited to the enforcement of pre-existing rules, since teams were receiving a lot more time on the power-play. The league-average power-play success-rate went from 16.5% in 2003-04 to 17.7% in 2005-06. Players were no longer held up in the corners or clutched and grabbed going to the slot while on the power-play.

Things have changed in just seven short seasons.

On Altitude TV’s broadcast of the Colorado Avalanche and Phoenix Coyotes matchup Thursday evening, Avalanche color analyst Peter McNab eluded to the fact that power-plays are not what drives a strong offensive team nowadays.

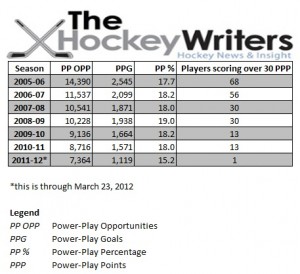

“There are less power-plays-per-game now than there was the year after the lockout,” McNab said. “Players aren’t scoring on the power-play like they were. There were 68 players over 30 power-play-points in 2005-06. You know how many there are right now in 2011-12? One.”

Let’s take a closer look at McNab’s theory. Here is a chart of how many total power-play opportunities and goals, as well as the league-average power-play percentage and total 30 power-play-point-scorers, were produced each season.

As you can see, power-play opportunities have taken quite the dip each season since 2005-06. With the exception of 2008-09, a season that saw nine teams finish higher than 20.0% with the man-advantage (there are usually about five or six teams that finish higher than 20.0%), the total power-play goals scored each season has decreased as well.

The most important point is that teams are staying out of the penalty box.

The reason for this is quite simple; the video coaches and players themselves have learned the game and found ways to beat the system without doing it illegally. Coaches and GMs have learned that speedy defensemen are more reliable than the slow but hard-hitting defensemen. High-powered offenses are being met by quick-footed defensemen who can keep up with the play while not allowing themselves to be beat.

Basically, players are doing exactly what caused the dead-puck era in the ‘90s; they learned how to beat the game. The trial-and-error period after the lockout is over. Teams have learned how to defeat a good offense with a nice, clean game.

This can be said for penalty-kills as well. The insane fights in front of the net that we remember with Tomas Holmstrom and Chris Pronger are all but over. Now penalties are being killed with Brooks Laich lying down in front of a Brian Campbell slapshot or Maxime Talbot blocking a cross-ice pass from Michael Del Zotto.

There are now talks of minor penalties being handed out for hand passes made in any location on the ice. While this would be a minor tweak compared to the changes made seven years ago, there is no doubt that this was brought up to hinder a team’s breakout from their own zone. Not only would it keep the puck in the offensive zone for the attacking team, but it would also give them a power-play.

This may allow for more power-play opportunities in each game next season but teams would just learn to adapt. Slowly but surely, teams will adjust and hand-pass penalties will disappear from the game entirely.

No matter what the rule change may be, heightened goal-scoring is a pipe dream as far as coaches and players are concerned.