This past April, Kevin Westgarth stood in the visitor’s locker room at the Prudential Center grinning ear-to-ear. The former Los Angeles King had just wrapped up a charity ice hockey game with several former NHL players. In the game he did something he had only done seven times during his NHL career – he scored a goal.

While he joked that maybe his three NHL employers, the Kings, Calgary Flames and Carolina Hurricanes missed out on some of his skills, they never expected him to score goals. Westgarth’s skill was always with his fists.

For Love of the Game

You probably can’t find someone who loves hockey more than Westgarth loves hockey. When he speaks of the game, it is transfixing. He describes the beauty of it – from its speed to its skill to its physicality – eloquently and with passion.

Growing up in Canada, the sport was integrated into his life early on. By the age of three he was on skates, and a year or two later he was playing organized hockey in rinks and on ponds in Ontario. “When I look back, I think I was on the ice a lot more than I was actually standing up and skating on it at that age – some people might argue that never really changed,” the 2012 Stanley Cup Champion said. “[But hockey was] certainly something I fell in love with really quickly.”

As a youth hockey player in his hometown of Amherstburg, Ontario, Westgarth dreamed of playing in the NHL. Over time he developed his hockey skills and learned he could hold his own when he dropped the gloves in Junior B. Unlike fellow heavyweights Tie Domi, Stu Grimson and the late Bob Probert, Westgarth went undrafted and opted for Div. I hockey in the United States.

But in the collegiate game, fighting leads to suspensions. So the 6’4″, 234-lb forward worked on his skills and his hockey sense at one of the top academic institutions – Princeton University – all while carrying the heavy workload of a pre-med major off it and prepping for his eventual post-collegiate career as an enforcer.

“When I knew that fighting was probably going to have to be part of my skill-set I took boxing classes,” he remembered. “I did boxing training at Kronk Gym, a legendary boxing gym, in Detroit. It was a heck of an experience. I knew I was in great shape after being in a 90 degree, humid gym after a whole summer.”

The greatest posed pic of two great Tigers @GeorgeParros and @KWesty19 #showyourstripes #TAGD pic.twitter.com/7Q1mbLQ4Kv

— Princeton Tigers (@PUTIGERS) November 24, 2015

Almost 15 years later, what he would tell his 18-year-old self? Westgarth, with a big laugh, responds, “Geez, maybe don’t do pre-med if you’re just going to go fight professionally for 10 years. It certainly would have made my college career a little easier. [But] I wouldn’t trade those four years for anything. If I could go back and tell myself what I was able to do – playing in the NHL, winning the Stanley Cup [with the Kings], playing overseas at the end of my career – I don’t think I would have believed myself. It’s an incredible life to have lived.”

The Art of the Fight

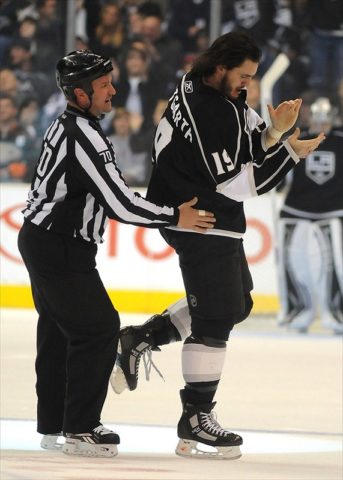

Always an academic, Westgarth looked at his role analytically. Over the course of his 10-year career that spanned time in the NHL, AHL, and EIHL in the United Kingdom, Westgarth fought in over 100 fights. He developed an open, easily adjustable style that always favored one side.

“The way I kind of carried my hands going into the fight – my left tended to be low and my right up near my chin,” Westgarth remarked. “I was never afraid to have as many tools in the toolbox as possible between body shots or jersey jabs or switching right to left. Inevitably, I liked to throw hard with my right hand and sometimes that opens you up [to get hit] and sometimes it gets you the win.”

And sometimes the decision to fight was easy – like when an opponent crossed a line with one of his teammates. Yet, other times the choice was a bit more complicated.

“There are so many pieces that go into this equation,” he noted. “Whether you’re up or down, home or away, what he exactly did, the momentum of the game – it was something that for better or for worse I probably over-thought it a little bit … But once you dropped the gloves and make that decision it’s man-to-man and that part of it was always simple. You just went in and tried to win the fight.”

A Brotherhood Among the Fighters

Fair to say Westgarth is not your prototypical heavyweight but he knew his place in the game and did it well. So well that the Kings petitioned to have his name on the Cup when they won. Westgarth initially didn’t qualify because he didn’t play enough regular season games, or a Stanley Cup Final game, due to injury.

While his teammates admired and appreciated him, he also knows he probably had more in common with the guy he was fighting, then the guy sitting next to him.

“You understand the day-to-day and the kind of the mentality that has to go along with it,” said Westgarth who faced fellow Princeton Tiger George Parros on a number of occasions. “Obviously you want to win because it gets your team going. It gets your team momentum and builds intimidation so there was never anything too personal for the most part. [Now] if a guy just rammed one of my teammates from behind and I had to go grab him, I probably wouldn’t be very happy and tap him on the back after that.

But a lot of the engagements between myself and the other heavyweights is usually started elsewhere. You stand in there and give it your best and when it’s over, it’s over and [you] tap each other on the back. That’s one of the most beautiful things I have ever experienced in hockey, the height of civility at the height of violence.”

That’s one of the most beautiful things I have ever experienced in hockey, the height of civility at the height of violence.

A Different Type of Ice Guardian

Today, more than two years removed from his last fight, Westgarth has shifted his role to the NHL’s front office.

Final pics from press event in China, plus an unofficial Kings Alumni Assoc mtg w/ Luc, Mathieu Schneider of @NHLPA and @KWesty19 of @NHL pic.twitter.com/ZSkVPav9pp

— LAKingsPR (@LAKingsPR) March 30, 2017

As the vice president of business development and international affairs, his main role is working to grow the game across the globe. But he also continues to protect his fellow players, and the players of tomorrow, by staying engaged in players transitioning post-career, player safety and concussions.

“I’d say that the 10 years that I played professionally was such an interesting one because … concussions were like, ‘alright try not to get a concussion,’” he said, noting that during his career he credited the training staff for addressing any head injuries he received properly. “You were more scared about breaking your orbital [bone around your eye].

“The biggest thing today is that players understand the risks, and I think will self-identify as having a concussion. Whereas, years ago you would never want to put yourself out of the game. It doesn’t tend to be an injury you can see, and so we’re inevitably built to push through whatever we’re dealing with if you can.

The extremely encouraging thing to me is that guys will acknowledge it … everybody understands now what the issues and the risks actually are … There’s a ton of work and a ton of science, a ton things left to understand and to improve on. But I think to see where we’ve gotten to already is really encouraging after clearly playing a game that’s been around for a long, long time.”

No Regrets

According to Hockeyfights.com, there was an uptick this past season in overall fights and fights-per-game. But who is actually doing the fighting? The role of the enforcer as a specialized position is dwindling in the NHL. Gone are the days of organizations utilizing one of their roster spots for a player who has limited ice time, and whose sole purpose is to police the game.

Questions abound as to why these players have been forced out of the game, and the subsequent ramifications, are still being determined. Regardless of where you stand on this issue, as seen in the award-winning documentary Ice Guardians, those that served as enforcers put in the time and the work, and have earned the respect of everyone in the league and in the stands.

“The enforcer epitomized so many of the great values that our game upholds,” said Westgarth, who mentioned the cyclical nature of the sport and its eras could lead to the role returning to the game. “It is that sacrifice, team above self, that willingness to do whatever you can to help the team, and protecting each other. That’s just core to ice hockey … I just hope that those values, and that character, isn’t lost as we lose that element that used to be housed in one guy. [It’s] incumbent on those of us, the community, that it isn’t lost.”

While some may question why a kid from Ontario, who went to Princeton and was studying pre-med, would choose to drop the gloves, just take a look at his Twitter avatar.

“I’d say that for kids it’s always that dream. You watch the Stanley Cup playoffs. You picture yourself being on the ice at any NHL games, any kind of elite-level hockey. You just picture yourself out there. You always want that to be the pot of gold at the end of your path … It was something that you always dream about. To be able to live so many kids’ dreams, and anybody that’s put on skates was pretty amazing.”

** originally published in June 2017