This article was originally published in March, 2013.

Picture yourself.

You’re a star hockey player in your home nation. You guided your underdog national team to an Olympic bronze medal against bigger, stronger, and more seasoned hockey teams. You become a living legend in your homeland, yet you have no rights as a citizen. What would you do to save your family and yourself from impending doom? Could one hockey tournament save yourself and your family forever? Would you strike a deal with the devil to make it all happen?

The Devil’s in the Details

1931 would see the IOC meet in Berlin to decide on a host for the 1936 Olympic Games. At the time, both the Summer and Winter Games were held in the same year by the same host nation (With Lillehammer being the the first Winter Olympics held apart from the Summer games in 1994). After two votes, Berlin was awarded the games over Barcelona, Spain. Although the games are known as a showcase for peace, harmony amongst all, and most of all an athletic showcase; no one was to know the unimaginable evil which was starting to brew in segments of German society in the early 1930s.

1933 would welcome the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany. The party, led by Adolf Hitler, propagated a message of hate towards the Jewish population of Germany, whom they believed to be the cause of German malaise following their defeat in the First World War . Although at the time Hitler had no interest in hosting the games, his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels believed that this would be an opportunity to showcase the “Aryan race” notion that Hitler had been driving into the German psyche during this time. This would be Nazi Germany’s showcase to the world.

The Germans would end the medal count in their Summer Games with 89 (compared to the USA’s 56); Jesse Owens, an African-American track athlete, would end up being the darling of the Games walking away with four gold medals in the 100m, 200m, 4x100m, and the long jump. Hitler also left his mark on the Games by denying Jewish athletes from participating in the Games (the only exception being Gretel Bergmann, a world-record holding high jumper), and this led to many Jewish and non-Jewish athletes from around the World and within Germany itself to boycott the Games, with organizations such as the Canadian Jewish Congress attempted to mobilize public support against Canada’s participation in the games.

Although the Germans would end up walking away with the medal count in Berlin, there would be no dominance of that magnitude by the Germans in the Winter Games in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, in Bavaria. Norway would end up leading the medal count with just 6 medals compared to 15 by Norway and 7 by Sweden.

The Olympic Showcase

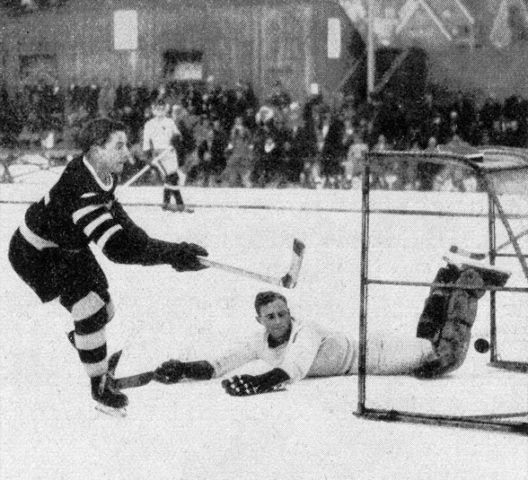

Ice hockey had finally started to blossom in Europe during the post-war periods. Canadians, many in medical school or in the Armed Forces, brought the game to locales for the first time. The game would flourish in post-war Europe, with countries such as Belgium, Italy, Hungary, Austria, France, and Czechoslovakia entering the traditional hockey fold with Switzerland, Sweden, the USA, Canada, and Great Britain, which had relied primarily on Canadian ex-pats to challenge Canadian domination in the late 1920s into the mid-30s. Through this blossoming, hockey would become one of the prestige events of the 1936 Games. The significance for these games were that they would also be the World Championships for 1936, a tradition that did not end until the late 1960s.

The German National Team was regaining its strength as one of the premier European hockey powers leading up to the 1936 games. The German team, able to compete internationally after a five-year banishment, was starting to regain the competitiveness and results the team saw prior to the war, which saw the German team medal in all four of the European Championships which took place prior to the start of war. The German team would find success in both the European and World Championships starting in 1930 when the team brought home a European Championship, while finishing runner-up to Canada at the World Championships. 1930 would be the starting point which would see the team win another gold at the European Championships (1934) while bringing home a bronze at the 1934 Worlds and the 1936 European Championships. The hero to many German fans was a man who would feel conflicted during this time, a man whose ancestry conflicted with modern-day ideology.

A Star is Born in Ball

There are few accounts on Ball’s life prior to his ascension to the top of German hockey, yet by those accounts Ball fell in love with the game later in life. Ball was born in Berlin to a German father and a Lithuanian Jewish mother on June 22, 1911. As a 15 year-old, he was exposed to the game for the first time, seeing a game between Wiener EV from Austria and the club he would one day lead, SC Berliner. A love of hockey was formed by watching a touring Canadian medical student playing for Wiener, Blake Watson, who had won a Memorial Cup with his Manitoba junior team a few years before. Ball would become mesmerized by Watson skating ability, and would watch on as Watson scored all four goals for his team as Wiener would defeat Berliner 4-3. Ball was hooked.

Ball would develop his ability over the next few years finally making his debut as a 17 year old for the second team of SC Berliner, the team he had grown up cheering for. In his first season on the second team, he would finish with 11 goals in 13 games, challenging for a spot on the top unit.

1929-30 would see Rudi Ball and his brothers Gerhard and Heinz start their reign of dominance of the German league, and European hockey in general. Ball would pot 33 goals to go along with 6 helpers in 24 games, securing his place amongst the elite of German hockey. His international debut would see Germany win a silver thanks to Ball’s tournament leading 5 assists at the 1930 World Championships, scoring his only goal of the tournament in a 6-1 defeat at the hands of Canada. Ball would walk away with his first international medal, a silver.

1930-31 would continue to see Rudi Ball strike fear into the opposition. Ball would lead the league again in scoring, and his feats in the German League was starting to be noticed by the European media. A French newspaper would state that Rudi Ball was the premier player of Europe, ahead of such stars of the time such as his teammate Gustav Jaenecke, Czech star Josef Malecek and his teenage idol, Blake Watson. Ball was becoming a star in his homeland, but how much longer could he stay in his homeland?

1930-31 would continue to see Rudi Ball strike fear into the opposition. Ball would lead the league again in scoring, and his feats in the German League was starting to be noticed by the European media. A French newspaper would state that Rudi Ball was the premier player of Europe, ahead of such stars of the time such as his teammate Gustav Jaenecke, Czech star Josef Malecek and his teenage idol, Blake Watson. Ball was becoming a star in his homeland, but how much longer could he stay in his homeland?

Although not quite a dominant scorer as he had been during the 1930-31 season, the 31-32 season would see Rudi put up respectable numbers of 18 goals and 4 assists in 25 games. Ball, however, once again shone for the German national squad, setting a goal-a-game pace in nine games for the team. Although Rudi, and his brothers for that matter, were well known throughout German hockey and sports circles, another German was making his own social imprint on the country.

1933 would see the rise of the Nazi regime to the Chancellorship of Germany. Hitler would strip all Germans of Jewish and mixed-Jewish ancestry of their rights and privileges as citizens. The Nazi regime, over time, would acquire land, farms, businesses, estates, and homes of their Jewish citizens to re-distribute amongst the regime. 1933 would also see Rudi and his brothers leave for greener, and safer, pastures leaving the German league, and National team, in their wake.

Ball Out of Hitler’s Reach

Ball and his brothers would start the 1933 season playing for St.Moritz in the Swiss League, where Ball would flourish into a superstar. He would score 12 goals in only 9 games, yet the town of St. Moritz and its rabid hockey base took to the brothers style of play, especially the undersized Rudi.

The Ball brothers would continue playing hockey outside of Germany, moving to Italy and joining the star-studded Diavoli Rosso Milano. In Milan, Ball would continue his dominance over the 1934-35 and 1935-36 seasons pacing the team with over a goal-per-game pace over both seasons while helping to lead the Milan-based team to a Spengler Cup championship in 1935.

Outsider at Home

With the Olympics approaching, Ball found himself on the outside looking in. He was not named to the German Olympic team, even though he had captained the team to previous successes. His Jewish ancestry and Hitler’s policies kept him off a team that so desperately needed his goal-scoring ability and leadership to compete with the Canadian and British hockey teams.

In early January of 1936, all signs pointed to the German National team playing the tournament without their best player and captain. To many within the hockey world, the Germans would not have the necessary skill, speed, and scoring to keep pace with the other Olympic teams. To Gustav Jaenecke, a prolific scorer in his own right and Rudi’s best friend and teammate at Berliner and on the National team, saw the writing on the wall. It was no secret that without Ball, the Germans would have no chance to repeat their success at the 1932 Games in Lake Placid, and Jaenecke helped plant the seeds for Rudi’s return to Nazi Germany.

Although originally named to the team, Jaenecke was refusing to play without his best friend; meaning Germany would be without its two top scorers. Realizing the team would not be competitive without their stars and attempting to win as many as possible to propagate their political machine, the Nazis and Ball struck a deal. By playing, Rudi’s family would be able to emigrate from Germany.

Through my research, there are conflicting accounts as to who Rudi met with. One account stated he had a meeting with Hitler, however this seems dubious at best. It is safe to say that a high ranking Nazi official met with Ball in Switzerland after the Spengler Cup, but it is known that Hitler would have the final say on whether or not he would play.

Although the tournament would be a disappointing one for Ball and his German teammates; Rudi scoring only twice while playing injured in 6 games, could only help Germany to a 5th place finish. Although this would be a blow to the German Olympic machine, Rudi expected his family to be released after the games.

Hitler kept his word. In late 1936, Rudi’s parents would settle in Johannesburg, South Africa. Ball and his brothers would continue to play for SC Berliner psot-1936, staying with the team until 1944. He would follow his parents and brothers to South Africa in 1948, helping to establish South African hockey.

It is safe to say that none of us will ever be put in such a situation as Ball, yet he has become one of the forgotten pioneers of European hockey. His excellence, both within Germany and Europe, helped to grow the game throughout Europe, and his lifelong love of hockey helped to establish it in a place few ever expected the game to be, South Africa. Ball would pass away in Johannesburg in 1975.

Rudi Ball would finally get his rightful place in hockey history by being inducted into the IIHF Hall of Fame in 2004.