Imagine doves being released. Horns blaring. Transit workers waving people through turnstiles.

That’s Dave Bidini, in his newest offering Keon and Me, imagining the triumphant return of estranged Maple Leaf Dave Keon to a Toronto sports organization and city that could use a healthy dose of sports catharsis.

Bidini, author of other hockey books such as Tropic of Hockey and The Best Game You Can Name, craftily weaves together a personal memoir with a biography of the most decorated Leaf in the team’s history.

Based in the NHL’s 1974/75 season, the eleven-year old Bidini encounters a school-yard bully (a Philadelphia Flyers fan, of course), and refuses to fight back – a tenet of the Dave Keon book of morality. But as Keon plays out his final season with the Maple Leafs, and as his relationship with the owner and organization deteriorate, Keon is faced with his own bully – one that he would not back down from – and yet in the process, would place himself in personal exile that he has barely peeked out from ever since. The boy and his hero, then, both experience at the same time a period of change and transformation, a parallel brought together in this creative piece of non-fiction.

Bidini from Keon and Me:

“The team was my albatross and millstone, a heavy thing slumped across my shoulders that I was required, somehow by birth, to carry…while this didn’t hold me back from leading a good life, it didn’t make it better“.

Bidini’s aim in the book is to help fill the void in the Leafs organization and the city left by the exiled Hall-Of-Famer. Keon’s relationship with then Leafs owner Harold Ballard has soured (and remains so) to the point where he will refuse almost all invitations and offerings from the Toronto club – who hasn’t won a championship since Keon won the Conn Smythe in 1967. The fact that perhaps the best player in the team’s history can’t bring himself to endorse the organization is a black mark on a team with more bruises than a supermarket apple. Bidini’s spit-shine and sleave-wiping is an effort to make things right.

Keon would win four Stanley Cups with Toronto along with two Lady Byng trophies as the NHL’s most gentlemanly player. Keon’s ability to play virtuous hockey and take endless physical abuse while remaining a practically penalty-free player inspires the boy not to fight back against his tormentor. As the story unfolds though, he comes to realize that changes are coming for both him and his hero.

“I thought there was a virtue in always being cool” – Fight Test, The Flaming Lips

From Keon and Me:

“(Keon) was a superstar for not fighting back…as a boy, I’d believed that I could build a life using Keon’s principles“.

For a “Good Ontario Boy”, the young Bidini lives in a fairly black and white existence in suburban Toronto. Goodness is equated with God, love, his family, and Keon. Badness is bullies at school, the Flyers, and Harold Ballard. The blind love young Bidini has for his team does not allow him to see that praising Keon for pacifism becomes an excuse not to stand up for what he already knows is right. Keon’s stubbornness is simultaneously courageous and limiting as interviews with former Leafs teammates reveal that his exile is a mystery even to them. So when Bidini’s school-age friends begin to doubt an aging Keon (who gets in his first career fight in his last regular season game in Toronto) young Bidini is forced to see things differently.

Near the end of the book, he tells a touching story about a climactic road hockey game against Bidini’s tormentor. One of his friends wonders why the bully is the way he is, telling the boys about a time when the appropriately named “Roscoe” needed company after a tragic death in his family. The thought everybody is sad together flashes through the young Bidini’s mind. Suddenly, the bully/victim dynamic, self-loathing Leafs fans, and Keon himself, amalgamate as a sad and lonely figure, yearning to be understood and to be brought back into the fold.

The author has a remarkable ability to make coherent the experience of a sports fan that looks to find meaning and value in a game played by professionals. He always gets the most out of his sports-fan experiences without sacrificing a full and happy life outside of that realm. Is he a writer, a musician, or a blue-blooded Leafs fan? Though Bidini’s experience as a fan is richly textured, one gets the sense that all aspects of his life are equally tended to by the versatile Torontonian. Somehow, that makes believing his story that much more gratifying. It’s easy to lament the sorry legacy of the Maple Leafs. The real challenge, one that is met in this book, is to make good out of so many years of suffering.

Keon and Me:

“After a while these discussions (with fellow Leaf fans) were nothing more than a laundry list of complaints, both parties feeling upset that it has come to this…the streets had fallen silent“.

To borrow a phrase recently used by current Leafs coach Randy Carlyle to describe goaltender Jonathan Bernier, Bidini “is at peace with himself” as a writer. Half of the tale is narrated by the eleven-year old, half by the full-grown author – though the transition is seamless. And the dichotomy speaks to a common contradiction many sports fans live every day: an incoherent love for a sport played both on the streets and by professionals for money.

The Hockey Passport

That seamless ability to also write from the perspective of a child provides tension to the scenes with Roscoe. Bidini is both the victim – and beneficiary – of what I call “The Hockey Passport”. The Passport is a kind of invisible badge that says “I’m a hockey fan” and it often will open doors for Canadians, whether for good or ill. The young Bidini and his bully are connected through hockey, though Roscoe at first uses it to his own advantage, reminding the boy that the Flyers are the team de jour. But hockey is also what binds them as seen in the final neighbourhood game.

Personally, I have gotten in to the wrong conversation countless times thanks only to the premise that I and the other party both enjoy the sport. Though it has helped many times as well. I was once mildly threatened by an larger boy in grade school who likely took me for a push-over (thank god he didn’t try). But when the two of us appeared at the same hockey tryout, and I made the team and he did not, an understanding and acceptance was apparent. Hockey does not tell us everything we need to know about an individual but, in Canada, it is indeed a measuring stick by which we perceive each other – and this is expertly illustrated in Keon and Me.

Number Fourteen Honoured

What Bidini wishes to accomplish, among other things, is to see Keon’s number fourteen honoured at the Air Canada Centre by the Leafs. All the greats are already there. Ace Bailey, Bill Barilko, Darryl Sittler, Doug Gilmour, Wendel Clark and more have a place in the rafters.

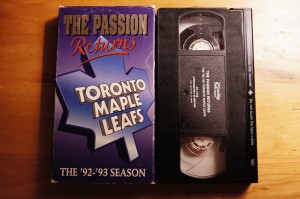

Many will remember that when Cliff Fletcher took over the team in 1992, he made a point of bringing history back to the city and organization. He retired the numbers of Bailey and Barilko, deciding to honour the history of a team that was coming out of the Ballard years. In the 1993 documentary The Passion Returns (about the year in which the Leafs met Wayne Gretzky and the Kings in the Conference Final), there was a sense that “bringing pride back to the Maple Leaf” was necessary in order for the club to climb out of a scourge of futility. Meanwhile in 2013, new CEO of Maple Leaf Sports & Entertainment Tim Leiweke made headlines by proposing to remove many of the reminders of past Leafs in the ACC, stating that the time had come to create new memories. Leiweke evidently felt the “millstone” that Bidini and many Leaf fans carry.

Rather than turn away, Bidini would have Toronto face its past. The good, the bad, and the shameful parts. Bidini makes peace with both the bully in his life and with the millstone that he proudly carries. Keon stood up to Ballard but ultimately turned his back on the team for his own reasons. Keon’s is a lesson that many hockey players today could learn from: the strength of character to turn the other cheek in a game of sharks. But again, Bidini helps Keon to face his past and the results are that kind of life-affirming sports catharsis that the people of Toronto have long been waiting for.

“For to lose, I could accept. But to surrender, I just wept and regretted this moment” – Fight Test, The Flaming Lips

Comments are closed.