Imagine that you are a young person, who has had some success in your chosen career, and have now been recruited by a new company and given a more high profile job. You show up to work, armed with your knowledge and experience, and things seem to go well for the first day or so. However, then it becomes apparent that your boss doesn’t trust you. Your boss is watching you like a hawk, and every slight transgression, mistake or violation of the rules is noted and broadcast throughout the organization, even though the rules keep changing. At the same time, colleagues with more experience, but less talent, have their mistakes overlooked. While they get more responsibility and accolades, you are demoted and have your responsibilities reduced, all in a matter of weeks.

Imagine that at the same time, your boss has put in a system of policies and procedures that makes the whole operation more vulnerable to errors. To make things work, you need to rely upon your fellow employees, but you can’t, as they are frequently reassigned to other tasks, sometimes multiple times in the same day. Sounds like a horror story, eh? Well, it pretty much sums up what life has been like on and off the ice for the Columbus Blue Jackets this season. The Jackets, who have woefully underperformed when compared to the expectations entering the season, have been mired in a protracted losing streak, dating to mid-November. While they have recently been playing near the .500 mark, there has been little consistency, at least in a positive way, and the fans have grabbed pitchforks and torches, looking for a victim to take the fall.

To be sure, there have been individual failure on the ice. Veteran blue liners Mike Commodore, Jan Hejda and Fedor Tyutin have struggled to regain their form. Rostislav Klesla has been beset by injuries, and young Marc Methot has failed to provide the quality minutes that were expected. Goaltender Steve Mason has been mired in a “sophomore slump”, exacerbated by the porous defense in front of him. However, watching the club perform, and listening to the players speak, the issue with the Blue Jackets seems more fundamental and structural. The transformation from a team that was 12 – 6 -1 and contending for the Central Division lead to the 14th place team in the West with a 21-25-9 record (and only after winning four of the last six) is a Jekyll/Hyde act of epic proportions. Absent catastrophic injuries, which the CBJ in large part have avoided, the explanation for such a collapse defies simple issues with personnel performance. A lack of talent is not the issue – six Blue Jackets are heading to the Vancouver Olympics for their respective countries — a number that trails only three other clubs. These are the same players that took the team to that 12-6 – 1 start. Something else is going on.

For better or worse, the mob has begun to focus its attention on coach Ken Hitchcock. Over the past 2+ years, the loudest applause at Nationwide Arena was reserved for the announcement of Hitchcock’s name. He was viewed as a savior of sorts, bringing a system of hockey to Columbus, and creating order out of the chaos that was left by President/GM/Coach/Sideshow Barker Doug MacLean. Of late, however, the applause has been increasingly muted, and the grumbling progressively louder. While management made initial statements of support, and have tolerated the losing streak well beyond what other franchises have endured (see Andy Murray in St. Louis), there has largely been silence from the front office of late. While the coach is always an easy target when the going gets tough, there is a growing sense in Columbus that Hitchcock’s demeanor and methods may be playing a bigger part in the current unpleasantness than was previously thought.

There is no question that Ken Hitchcock will be in the Hall of Fame someday for his coaching exploits. With 1000+ games behind the bench and over 500 victories, he is rightly considered something of a coaching icon. He is intelligent to the point of being cerebral. The same intellect that makes Hitchcock intriguing can also lead to a measure of arrogance and stubbornness. The same accomplishments and reputation that punch his ticket to Toronto can lead to resistance to change on his part, and perhaps undue deference by those around him. Where previously there was unquestioning allegiance to “Hitch Hockey”, as it has come to be known, fans and media are beginning to ask the tough questions, and are not necessarily thrilled with the answers they are getting.

At it’s heart, the situation in Columbus boils down to one word — Trust. Coach Hitchcock is not, by nature, a trusting soul when it comes to players, particularly young ones. His Stanley Cup club in Dallas was a largely veteran squad, with the average age significantly north of thirty. It is with veterans that he is the most comfortable, and if pressed, he will grudgingly admit that foible. He is also more prone to trust players with size and “grit” than

smaller players or “skill players”, a term he uses almost derisively. What he is less willing to admit to is the administration of a coaching standard that differs for veterans and youngsters. This season has been replete with examples of the double standard that applies to the youngsters, which is an unfortunate turn of events when you are dealing with one of the two youngest clubs in the league.

Of course, the most notable example this season was the handling of 2008 first round pick Nikita Filatov. In the 2008-09 season, Filatov played eight games with the big club, notching four goals (including a hat trick) and 8:07 of average ice time before his pre-determined assignment to AHL Syracuse for seasoning and beefing up. After a successful year in the minors, great things were expected of Filatov, with the primary concerns focused on his diminutive size. While Filatov reported to camp somewhat bigger than last year, those concerns remained. In the meantime, Hitchcock and Filatov were battling over Filatov’s adherence to Hitchcock’s defensively-based system (more on that below). Turnovers or mistakes resulted in immediate benching, and the winger was made a healthy scratch in numerous games. The coach explained that those games were expected to be “heavy” or “weighty” (Hitchcockian prose for “physical”). As his ice time dwindled, Filatov’s frustration increased. His average ice time actually decreased over his brief stint on the parent club the prior year. As has been well documented, the impasse continued until GM Howson, somewhat reluctantly, agreed to allow Filatov to return to his Russian club for the remainder of the season. Since then, Filatov has been reported as saying that he will not return to Columbus as long as Hitchcock is the coach.

Whether or not Filatov was ready physically for all of the demands of the NHL, and notwithstanding whatever disagreements coach and player had, most observers agree that Filatov was not given a fair shot to show what he can do. Single digit ice time numbers are simply insufficient to allow skill players like Filatov to get comfortable with the flow of the game, learn the flow of linemates, and the myriad other situations that arise in the course of a game.

If this were an isolated incident, it could be written off to a personality conflict between a prima donna star in the making and a veteran coach. However, the same scenario has played out repeatedly as the season has progressed. Defenseman Kris Russell, who suffers the affliction of being both small and young, was benched for a series of games, despite being one of the few blue liners who demonstrated the ability to exit the zone and create transition. His game has taken off since he has been given the opportunity, which has arisen partly due to his good play, and partly due to blue line injuries. A similar story more recently has played out with newcomer Milan Jurcina, acquired from Washington in the Jason Chimera trade. An imposing physical presence, the 23 year old has impressed most observers with is unexpected speed and a point shot in the Souray/Phaneuf category. Yet, there he was — scratched four consecutive games. Hitchcock attributed it to “difficulty adapting from Washington’s style of defense.” (Uh, please check standings and GAA to see who should be adopting which system).

The poster child for this inability to trust younger players may well be center Derrick Brassard. After posting phenomenal numbers early last year, and earning NHL player honors for October, he sustained a season-ending shoulder injury against Dallas. Entering this season, he was slated as the top line center. He debuted in that role this season, stayed their two games, was moved to the second line for Game 3, then moved back to the top line for a few games. By Game 9, he was on the fourth line, wondering what had happened. Since then, he has bounced between the lower three lines, with his ice time hovering around the 14:00 minute mark. Even that number is inflated by some more recent time on the ice. However, even increased minutes do not guarantee trust. In the last game against Nashville, Brassard , who played a magnificent game and earned First Star honors, was nowhere to be found on the ice during the third period, and ended up with just over 12 minutes of ice time. Coincidentally, Nashville just happened to close the gap from 3 – 0 to 3 – 2 during that time frame.

Raffi Torres, the best shooter on the club, and tied for third with 16 goals, sees even less ice time than Brassard, and has been relegated to the fourth line more often than not. He brings energy to the ice, and a second line of Brassard, Voracek and Torres has performed very well the few times it has been put together. There is simply a lack of trust on the part of the coach that is beyond the understanding of players and fans. In a recent game against St. Louis, Columbus had a two goal lead with 1:30 left in the game, and the Blues had pulled the goaltender. Torres had scored two goals in the first period, and players and fans were screaming for Torres to be given the chance to notch his first hat trick. He remained on the bench. After the game, Hitchcock dismissed the issue, stating merely that he had a game to win.

If this were a situation where the youngsters were struggling, and could not crack a lineup of highly performing veterans, the lack of trust would be understandable, to a degree. However, that has not been the situation in Columbus. Commodore, Hejda, Tyutin have struggled mightily on the blue line. Huselius has been streaky in the offensive zone, but largely a disaster in his own zone. While youngsters are scratched, benched or sharply curtailed in ice time should they make a mistake, the veterans are encouraged to “play through it”, even when their play is markedly inferior to the younger players. You thus have this infernal circle of distrust arising. The coach distrusts the young players that make up the core of his club. The players, in turn, cannot trust the coach to provide them with what they perceive to be a fair chance. When the bulk of your roster is under 25 years of age, the corrosive effect in the room is significant.

The flip side of the trust issue is that those players that are favored with trust are over-utilized. Rick Nash leads the NHL among forwards with just under 30 shifts per game, and only defenseman Fedor Tyutin averages more TOI than Nash. With a significant part of Nash’s time coming on the exhausting penalty kill unit, it is no wonder that Nash sometimes looks exhausted. Tyutin, Commodore and Hejda were similarly run into the ground last year, and had nothing left by the time the playoffs came around. The same was largely true of goalie Steve Mason. Ironically, all four have struggled this season.

Another by-product of the “trust gap”, at least in Columbus, is the endlessly changing spectrum of lines, practice philosophies and game strategies. Hitchcock, for all of his external coolness, is feeling the heat, and has frankly been scrambling to find solutions. Never a patient guy, he seems incapable of retaining forward line combinations for more than a game or two, and more frequently will have multiple changes within a game. He speaks publicly of “rolling four lines”, but rarely does it. He speaks of a “win and you’re in” philosophy for the goaltenders, but abandons it quickly. Umberger moves from center to wing and back to center. He bemoans the lack of practice, then cancels practices or makes skates optional. It has all combined to provide a sense of turmoil that the fans and media, let alone the players, find disorienting.

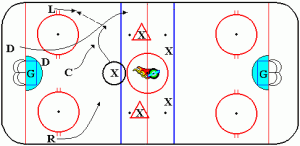

The final contributor to the quagmire of the Blue Jackets’ current situation is the system of hockey that Hitchcock is attempting to implement. The highly technical, defense-first system, which incorporates the much-despised neutral zone trap, among other elements, subordinates scoring to checking. This system took him to a Stanley Cup with Dallas, and he is steadfast in his adherence to these principles.

When Hitchcock came to town, “the System” was applauded, and needed. Other than Rick Nash, the talent pool was relatively thin, and the other talent that existed had been largely misused by Doug MacLean. Hitchcock’s system gave structure to the game for the Blue Jackets, and provided something to fall back on when talent was lacking. Such is not the case today, but the coach has not shown much inclination, at least formally, to adjusting his system to the talent pool.

On their way to their best start in franchise history this year, the Blue Jackets were not playing true “Hitch Hockey” –instead pursuing a more open, free flowing style. As a result, the Jackets found themselves near the top of the league in scoring — unfamiliar territory for them, or for any Hitchcock-coached team, for that matter. The defense, however, was something else entirely. The Jackets were giving up uncharacteristically high numbers of goals in their losses. Hitch seized on this and put the clamps on. No more free-flowing offense. Unfortunately, what happened was that goal production plummeted, from near the top of the league to 28th at its nadir. In the meantime, while the goals against average went down somewhat, it did not decrease as much as needed to offset the lack of offensive production. The tailspin continued.

Recently, the Jackets players have seemingly taken matters into their own hands, adopting a more open style, reminiscent of the beginning of the season. Their goal production has improved, and their goals against average, while still near the bottom of the league, is headed in the correct direction.

An inherent problem with Hitchcock’s system is its fragility. It strongly depends on everyone on the ice being in lockstep. As Captain Rick Nash observed: ” . . .If we have just one guy not on the same page on a line, it causes a problem. . . We have find a balance between a focus on checking and scoring.” Attempting to implement such as system with any team is a challenge, let alone a team composed primarily of youngsters, many of whom are the dreaded “skill players.” Also consider that this system has not yet been shown to work consistently in the post-lockout NHL. Previously, teams were free to restrict the speed of the opponent through aggressive body and stick play, which would be whistled today. Hence, teams could rarely enter the neutral zone with speed, and it was much easier to clog up the flow of traffic. Properly played, offensive production slowed to a crawl . . .usually for both teams.

In today’s NHL, teams employ a much quicker entry into the neutral zone. While the trap can still cause disruption and turnovers, it can also lead to odd man rushes in a hurry. One quick pass down either wing, and the race is on, as the defenders must now scramble from a largely static position in the neutral zone to chasing. The result is rarely positive for the defensive team. In today’s league, the trapping style is far harder on the defending team, calling into question whether it can successfully be utilized as a basic system. What seems far more likely is that it needs to be but a piece in the arsenal, akin to the full court press in basketball — used at strategically important times, but not as a steady diet.

How does this all come together to explain the Blue Jackets’ current dilemma? First, consider the example at the start of this article. How would you feel attempting to work within such an environment? The players come to the Blue Jackets knowing how to play hockey. They have ability, they have skill. Sure, there is a lot to learn about playing at the NHL level, but they would not be here without the talent to succeed. They start the season, and have success. Sure there are blips, mistakes, stupid plays, but at the end of the day, they are winning twice as many as they are losing, despite some suspect goaltending and downright awful blue line play.

What happens next is that the boom is lowered. Now there is insistence on Hitchcock’s system, which he will tell you is “the Right Way” to play the game. Every mistake is potentially lethal. Players start thinking instead of reacting, afraid to overcommit, terrified of allowing a goal that would not only result in a loss, but result in reduced ice time or a scratch. Instead of a loose, confident team, they become a scared, hesitant club. As they become more scared and more cautious, the mistakes increase instead of decrease.

This phenomenon is not limited to sports or the hockey rink. If I may be allowed a personal example, I will use my mother to illustrate the point. Her parents emigrated from Germany in the 1920’s, and my mother grew up speaking German and English fluently. When I was in middle school, she went back to college to get a masters degree, and needed language credits. Intelligently taking the path of least resistance, she chose German. Unfortunately, after two or three courses, her fluency in the language disappeared! Instead of relying on her instincts to “hear” what was correct, her mind was now filled with scores of grammatical rules which came to the fore when she tried to speak. Though she was understandable, she never again spoke with the same fluency.

The Jackets are suffering from the same problem. They have lost their inherent fluency. Watching them when they have adopted an up-tempo style in recent games is like watching an entirely different team. However, Hitchcock refers to such games as “track meets”, and will be quick to single out that style of play as the culprit when they lose. A recent 6 – 5 loss to Chicago presented precisely such an opportunity. However, to the sellout crowd assembled, most appeared enthralled by the style. But for some marginal goaltending and some maddening lapses down low in the defensive zone, Columbus played the Blackhawks to a standstill, a considerable feat, considering that few clubs play that aggressive, puck possession style better than Chicago.

Indeed, the long term answer to the Blue Jackets’ ills may be found in the approach Chicago adopted. Two years ago, when the organization brought in Toews, Kane and a number of other youngsters, they made a commitment to go with the youth, let them learn through their mistakes, and enable them to become familiar with each other on the ice. In their rookie year of 2007-2008, Toews averaged 18:40 on the ice and Kane 18:21. Versteeg, who came up late in the year, averaged 15:52. Those numbers have largely stayed the same over the past two years, and the results are apparent. They know each other, have learned from mistakes, and have that intangible confidence. They are trusted by their coach, and they return the trust in the form of their performance. This is a sharp contrast to the way the Jackets’ youngsters have been handled. Hockey is largely a game of accumulated memory, and the more ice time experience that can be lodged in the brain, the more readily a player can react when that situation arises again. The 3 and 4 minutes of difference in ice time per game between the Chicago youngsters and the Jackets’ youth translates to almost 20 games worth of playing time per season. Not insignificant.

Of late, Ken Hitchcock has spoken more of playing the younger players, and has even had one of the assistant coaches take over the primary communications with the youngsters. However, the words have not translated into action. They youngsters are still not trusted, and will usually be found on the bench at critical junctures of most games. Delegating communication to assistants is not change — it is abdication of responsibility. Hitchcock needs to turn over the reins to the youngsters, let them make their mistakes, and learn together. Unfortunately, this is something that should have been happening since Day 1. If he can’t or won’t do that, GM Scott Howson and President Mike Priest will have some hard decisions to make. Ultimately, however, they need to be guided by the issue of trust. Can an organization progress when the coach cannot find it within himself to trust the majority of his players? How can players put trust in a system and a coach that does not recognize them or utilize their talents? With only a single playoff appearance on their organizational resume, the Blue Jackets can ill-afford to get this one wrong.

Insightful and accurate analysis. The strength and utility of Hicthcock’s system can become a detriment when taken too far. As for Zherdev and Filatov, they would have put butts in seats and the CBJ would have been appreciably better off financially losing 5 to 6 rather than 1 to 4.

PS – my seat license expires in June 2010 and after 10 years of waiting for the CBJ to move to the next level, i am movin’ out.

Of course the players are responsible for their effort, but they also need to be given the tools that will enable them to succeed. Foremost among these is stability–particularly during — and that is the function of the coaching staff. Put in a system that rewards talent but is defensively responsible. Chicago, San Jose, Washington are three examples of systems where offensive skill and speed is displayed, but defensive

Mason is 21 years old, and is learning how to deal with adversity. He is an extremely passionate competitor, and sometimes his statements seem harsher than he intends. He takes individual failure very personally. Nash straps the entire team to his back and plays in every situation. He may not be as vocal as some, but his example should inspire.

Modin and Boll are there because they are “Hitch” players — relatively big, focused on contact more than skill. IMHO, Boll has no place in the lineup, and Modin is an afterthought.

I don’t fault Howson for Malhotra leaving — no way he was worth the money he was asking at the time (as is validated by his $700K contract in San Jose). I do think that he was overly optimistic in projecting the leadership role Modin would have, given his injury history. The Peca story is overblown — nobody else picked him up either. Now if it was Peca instead of Boll, I could see that. I really think that Howson hoped that Commodore, Hejda and Tyutin would step forward more this year.

I have been in the locker room with the players, and they are as frustrated as the fans. In fact, I think they have frustrations that we never see, and they will certainly not air out in public, relating to dealing with Hitch’s inconsistencies and a flawed system.

Did you the game last night, it’s now official – MIKE COMMODORE HAS RETIRED. Unfortunately he has not announced it and he is still collecting a hefty paycheck.

You are correct about Hitch, of course but there are so many other problems. The primary issue is motivation. How else can you explain the inconsistendcy and the lack of sacrafice and willingness to do the dirty work.

Mason is a prima donna head case.

Boll is a middlewiight in a heavyweight’s job.

Nash has no more effect on the team’s psyche than the bus driver.

Modin has a wing named after him at Ohio Health. The list goes on.

This team is weak and lacks any heart or leadership. Did you see the game last night? The first line managed only 3 shots on goal?!?!?! WTF?

I would like to hear your thoughts on the team leadership at this stage. I know how you feel about Hitch and his coaching style, but at what point does Rick Nash or any of the others take responsibility and stand up and actually say “Enough is enough”…… at this point, they don’t even seem to be playing for pride anymore.

The last player with any heart on this team was traded to Washington. It’s going to be fun to watch him make a run at the Cup alongside Ove. Now that’s an exciting team to watch. It was also fun to watch Shelley and Manny play for the Sharks last night……. I’m hopeful for a Sharks/Caps final.

Wow, that’s exactly how I feel at work. I’m not appreciated, they don’t recognize my skills, they constantly tell me (and everyone else) when I do something wrong. And I only make 18,000 a year (gross)….which is actually 12,000 take home after social security and state taxes. Maybe you could write a story about how home healthcare providers (aka caregivers) should receive millions of dollars a year and then justify it by telling everyone how under appreciated they are!

This is quality analysis and writing – and not just because I agree with it. I was one of those that applauded Hitch’s arrival. But that being said, he is not (sadly) the man for the job today. The CBJ’s experience with Russian imports has not been good to date, but Filtatov is not Zherdev and the reality that Hitch is not willing to incorporate such a talent into his team is telling.

I love your work. Too bad our local paper can’t analyze the team and the game as well as you guys. Keep up the good work.