I worry about my kids playing hockey. Sometimes I fear my love for the sport will influence them too much. Other times, I am concerned that a certain hockey mentality will shape their character in ways their mother won’t like. Most of all, I worry I am encouraging them to play a dangerous sport.

All sport involves some sort of risk, of course. Hockey comes with a culture attached. Not all of it is good. It is a sport where Don Cherry still makes money on videos extolling hard hits and hockey fights. Fans and players alike accept concussions as part of the game. Late checks are encouraged, hidden behind the euphemism “finishing your check.” While speed and finesse are increasingly seen as the future of hockey, the present-day reality is one that too often embraces problematic values.

Enter Ken Dryden. Brett Popplewell argues Dryden’s latest work, Game Change, is the most important book about hockey in decades. It is a biography of a player, a history of the game, and a love letter to the sport. Most of all, it is a cautionary tale. It is the perfect Christmas gift for the hockey fan in your life. It is hard to put down and impossible to ignore.

Check out the book at Amazon:

Game Change: The Life and Death of Steve Montador, and the Future of Hockey

Ken Dryden and The Game

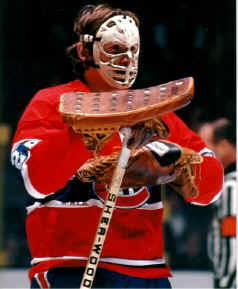

Key Dryden was the goalie of the Montreal Canadiens for most of the 1970s. In seven seasons, he won both the Calder Trophy as top rookie and won six Stanley Cups with Montreal. He played for Team Canada in the famous 1972 Summit Series against Russia. In his first year of eligibility, Dryden was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1983. The Montreal Canadiens retired his number, 29, on Jan. 29, 2007. He was inducted into the Ontario Sports Hall of Fame in 2011 and recently honored by the NHL as one of the 100 Greatest NHL Players in history.

Off the ice, Dryden is a lawyer, author, speaker, and occasional lecturer at McGill University. He served as a Member of Parliament between 2004 and 2011. His first book, written during his playing career, is called Face-off at the Summit. Written in diary form, the book outlines his experience in the famous ’72 Series.

Hockey Culture

While he has written seven books in total, his best-known work to date is The Game. Published in 1983, the book details events surrounding the 1978-79 Montreal Canadiens, including the lifestyle of a professional hockey player. The book describes the pressures of being a goaltender and gives readers a behind-the-scenes look at a team that would eventually win the 1979 Stanley Cup. The book is more than that, however. Dryden offers a meditation on hockey’s special place in Canadian culture. This is a theme he has returned to in subsequent books, including his latest.

Game Change: The Life and Death of Steve Montador, and the Future of Hockey

Dryden fuses a biography of the journeyman hockey player with a call to save the lives of athletes who are vulnerable to brain damage caused by concussions. He argues that at hockey’s core there has always been a historic compromise between performance and safety. Right now, that compromise is out of whack. Can this book re-balance these competing values? The book intertwines three stories.

The Career of Steve Montador

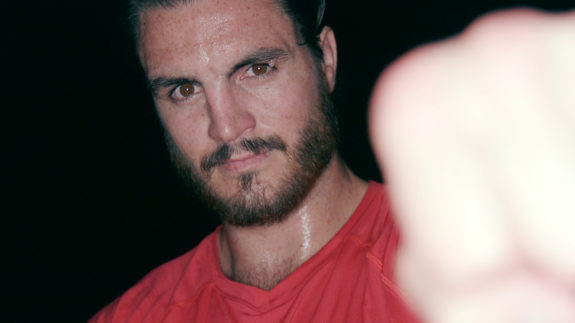

As the title suggests, first and foremost, the book is about the career and untimely death of Steve Montador. Dryden never met Steve “Monty” Montador. It is hard to tell, though. A decent, curious, “glue guy,” Dryden spends a lot of the book tracing his experiences in youth hockey. His parents, billets, teammates, and friends are all part of the story. Monty’s slide from a fun-loving, quintessential, hardcore NHL “hockey guy” to a depressed, manic, and deeply damaged young man comes too quickly. We know him by the time his chosen career leads to his downfall.

The book begins by chronicling the inspiring story of an unlikely prospect who makes it to the show. What starts as elation is tempered as the injuries mount and Montador’s physical and mental health begins to break down. As I read the book, it was hard not to think about the documentary film “Ice Guardians“. In both the film and this book, the desire to play the game overwhelms the challenges of basing a career on the more physical parts of the game. Montador fought from time to time, but he was no goon. He played 571 games on six NHL teams between 2001 and 2012 and scored 131 points as a No. 5/6 defenseman.

Head Trauma and Off-Ice Struggles

The book delights in the relationships that are made within hockey, the power of being on a team and the ways in which the game is woven into the fabric of Canada and Canadians. However, it is not all come-from-behind wins and adulation. As the book progresses, events begin to foreshadow the tragic outcome readers know is coming. Popplewell offers this take:

You can feel the impending doom mounting as Montador suffers a concussion here, another there. He battles through the residual haze, struggles with demons, then comes back stronger on ice. There are touching moments throughout. Like when he loses his place on the Calgary Flames and suddenly he’s standing alone with his equipment as the team bus pulls away. Or when he later realizes he has a drinking problem and quietly checks himself into rehab during the 2006 Olympic break.

There is a danger that by tying a book about player safety to an individual, that individual will get used as some sort of vehicle to be conveniently packaged to make what is ultimately a political point about hockey. Thankfully, in Dryden’s capable hands, that doesn’t happen. Dryden treats Monty’s memory with great care and deep respect.

Peaceful Presence

Dryden’s description of Steve Montador is based on interviews friends, family, coaches, and teammates. A portrait emerges of someone who felt grateful to play the game he loved but was troubled by his replace-ability. He was a deep thinker, articulate, and funny. He wanted to improve as a player and as a person. While he played a physical game, off the ice he had a peaceful air about him. He touched those who knew him in ways that are difficult to untangle.

Dryden includes excerpts from the journal Montador kept during his last years. This helps the reader better know Montador and is a unique window into his frame of mind. These entries recorded his hopes and fears for the future and outlined his efforts at self-improvement. It is sad to read his words and to realize that he passed just days before becoming a father.

I didn't know much about Steve Montador when he was in the NHL. Ken Dryden's portrayal of him in Game Change made me wish I had known him.

— Steve Simmons (@simmonssteve) October 25, 2017

Montador died on a February night in 2015 at the age of 35. His death was the culmination of a downward spiral of drug use, prescribed and non-prescribed, alcohol abuse, and interactions with friends and teammates that left everyone increasingly uneasy. His alcoholism had led him to try treatment, but his increasingly manic behavior meant sleepless nights and drug and alcohol binges. Where once he was a calming presence, in his last days he was unsettled and unbalanced.

A History of Head Shots

A second theme throughout the book is the historical context Dryden offers about the game of hockey itself. There are two issues here. The first is around fighting. While the notion of a protector existed as far back as the 1920s, the concept of an enforcer can be traced to the 1970s and 1980s and the expansion of the league. More teams meant more players. More players meant room for tougher players. The Philadelphia Flyers during the “Broad Street Bullies” era took the intimidation game to another level. This led to an arms race and the center-ice fight, and staged fights of the 1990s, where announcers gleefully introduced a “super heavyweight bout.”

The second theme is around how the speed of the game and the physicality have combined to make defensemen particularly vulnerable to late hits. Dryden shows how hockey evolved from a rough-and-tumble game in which players took few hits to the head over the course of a season into its modern incarnation where they may take multiple concussive blows in a single shift. Dryden points out that we are all at fault here. Wayne Gretzky, the WHA, the Soviet Union, Don Cherry, Broad Street Bullies and even he, the one-time Canadiens backstop, all played a part here. It’s on fans too.

The Joys of Pain

As the film “Ice Guardians” points out, the crowd roars when there is a fight or big hit. It is different somehow than the sound a crowd makes after a goal is scored. As a way to access our instinctive nature, it is primal and tied up with our reptilian brain. While it may be an evolutionary holdover, sport as conflict engages old and powerful notions of good and bad. Indeed, there is a visceral joy in the power and danger of those encounters. It is clear this joy brings terrible consequences.

Hours after he was found dead in a rented Mississauga home, Steve Montador’s brain was removed from his head and sent to the Toronto General Hospital to be studied. This was a promise he had made before his death. Like Reggie Fleming, Bob Probert, Derek Boogaard, and hundreds of other professional athletes over the past 15 years, Montador’s brain was riddled with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE. The growing recognition of the connections between traumatic brain injury, mental health, and substance abuse means coming to grips with some uncomfortable truths. For hockey fans, it means confronting both the history of the NHL and what reasonable steps can be taken to preserve the elements of the game we love.

Manifesto for Change

The third theme is tied up with developments in medical science and the future of hockey. The fact is we simply know more today than in the past. fMRIs and PET scans provide visual proof that something is wrong in the brain. There is a worry here that the red flag of CTE may be used as a shield, deflecting attention from the clear and present dangers in the short term. Anxiety, depression, memory loss, and addiction are all associated with repeated blows to the head. What should be done? Dryden proposes some dramatic fixes.

The last chapter of the book is a direct challenge to NHL commissioner Gary Bettman. Dryden identifies him by name as the only person who can actually draw this troubled chapter in hockey’s history to a close. Bettman is celebrating 25 years as NHL Commissioner and has overseen both successes and controversies. Dryden identifies what some may see as an existential threat to the game. “Two small changes,” Dryden writes in the book. “No hits to the head; no finishing your check.”

Just finished Ken Dryden’s book “The Game”. Never knew Steve Montador,found myself thinking of him and his life a lot. As for Ken’s suggestions, it’s more than reasonable to think these could make impact without altering what fans, sponsors,etc love about the game. Excellent read

— Ray Ferraro (@rayferraro21) November 11, 2017

Cultural Change and Complications

What we are talking about here, according to Bob McKenzie, is nothing less than a cultural sea change in hockey. This will be a problem for a sport which is perhaps too tethered to the recent past. For McKenzie: Any hit to the head is a bad hit to the head; any hit to the head should be a penalty. The reason? The fallout from hits to the head can be so severe and life-altering that whatever impact the new rule would have on how the game is played simply pales in comparison. It is hard to deny Dryden’s powerful warning that by delaying taking action “we waste careers and lives.”

Will Game Change be the catalyst to bring about real change? It should. However, there are at least three challenges to meaningful change.

Challenges and Complications

The first is that for many, there is an inherent and assumed risk associated with professional sports and specifically hockey. This means the onus is on the players. The argument here seems to be since there are numerous efforts at awareness and education about the risks of concussion, if you want to play professional hockey you accept the risks. Indeed, it seems strange that the association that is mandated to protect the interest of the players has not been more vocal on this issue.

The second is that while the history of hard hits and fights extends only to the 1970s, it has become ingrained in many fans’ minds as an essential part of hockey. This feeds the narrative that not wanting to be complicit in a rising tide of brain injuries is just another example that we are all becoming weak little “snowflakes” who need to toughen up.

The third challenge is perhaps the greatest. Who will decide when it is a late hit? Can players stop themselves in time to avoid contact? How can you separate a “good” body check from one that results in a hit to the head? The NHL can’t figure out goalie interference, let alone offside calls. How can they find a way to retain the physical part of the game while doing a better job of protecting their players?

Is Gary Bettman Up to the Challenge?

Dryden recounts two stories that suggest his faith that Bettman will step up here may be misplaced. Ths first occurred in 2011. After Sidney Crosby’s concussion at the Winter Classic, Bettman faced scrutiny from the media. Bettman retreated into lawyerly nitpicking, questioning the questions and disputing the premise of any questions directed at him.

The second was his response to Richard Blumenthal, Democrat of Connecticut and the ranking member of the Senate’s Consumer Protection subcommittee. In 2016, Blumenthal sent Mr. Bettman a letter asking pointed questions about the league’s position regarding concussions and CTE. Responding to written questions from a United States senator about the effects of concussions in hockey, Bettman continued to deny a link between concussions and CTE. The arrogance of his response to a sitting Senator was startling, even in Bettman-adjusted terms.

Ultimately, Dryden believes that Bettman must be convinced because he sets the direction not only of the NHL but of hockey around the world. Only he can lead on this issue. The challenge is that Bettman never played the game. Moreover, fans treat Bettman with suspicion. He gets booed. A lot. How will he respond to the discovery of the first case of a living person identified with CTE? The research seemingly cements the relationship between contact sports and brain damage. It will have profound implications for the NHL.

MIA: The NHL Players’ Association

Perhaps a more logical change agent here is Don Fehr of the NHL Players’ Association. It is unfathomable that the only organization with the mandate to represent the interests of the players is seemingly silent on an issue which represents such a danger to players’ long-term physical and mental health. Yet, as with the issue of reducing fighting in hockey, it appears the NHLPA is again missing in action.

For example, in response to yet another story of a former NHLer who is struggling with addiction, mental health, and homelessness, the NHLPA is nowhere. The investigative story about Matt Johnson, a 42-year-old former Minnesota Wild captain, broke a day before NHL Alumni Association executive director Glenn Healy was scheduled to meet with NHL deputy commissioner Bill Daly Thursday to discuss improving the physical and mental health care available to retired players. The NHL Players’ Association was not scheduled to attend the meeting.

It is possible the NHLPA will revisit this issue when the current collective bargaining agreement between the NHL and the NHLPA expires on Sept. 15, 2022. Current players may join former players currently involved in a class-action lawsuit against the NHL to press the NHL to do more. This might include devoting resources to study this issue, improving the concussion protocol, or perhaps taking the sorts of measures suggested by Dryden. In the meantime, this issue isn’t going anywhere.

Youth and the Future of Hockey

Dryden concludes the book by describing how much he loves to watch his young grandson play hockey. He concedes part of his motivation to write the book is to contribute to a culture in which his grandson isn’t at risk. Where he can play the game without fear of a cheap shot, or a legal check that changes the way he plays the game. Whatever the broader implications of this debate, every day we wait is another day a player is being placed at risk. Bettman’s legacy can’t just be about increasing profits, expanding visibility, and pursuing expansion.

Perhaps the NHL, players, and alumni can find a way to re-balance the historic compromise between performance and safety. While protecting the current generation of players is important, perhaps more important is protecting the youth who look to them as heroes. Steve Montador is not the last player to have suffered head trauma from hockey and been unable to get his life on track. Ken Dryden has done a remarkable job of linking the game we love with outcomes we can no longer ignore.