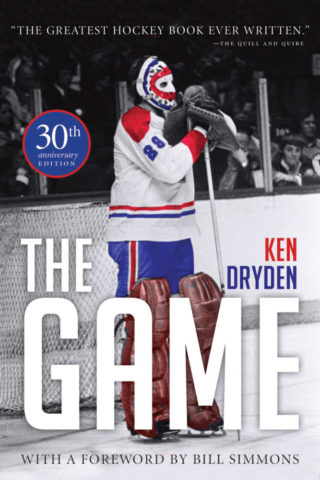

If you look at a list of all-time great books about hockey, invariably, Ken Dryden’s The Game will be in the top 10. The book is actually number nine on Sports Illustrated’s list of the 100 best sports books of all time. The only other hockey book to crack that list—which, complied in 2002, is admittedly old—is Game Misconduct by Russ Conway, which comes in at number 92. One list calledThe Game “the best sports book ever written by a participant.”

The accolades are well deserved.

Dryden, an All-time Great Goalie

First published in 1983, and reissued for its 30th Anniversary in 2013, The Game recounts one week at the end of the 1978-79 regular season. We follow Dryden—the goalie for the Montreal Canadiens—on airplanes and buses, in locker rooms and motels, and on ice for practices and games. The Canadiens have just won three consecutive Stanley Cups, as well as two Cups earlier in the decade (1971 and 1973), and Dryden is coming to grips with his decision to make this season his last between the pipes.

Dryden’s retirement at age 31 was remarkable. Not only was he at the top of his game, he was the most decorated goalie of his era. He won a total of six Stanley Cups, five Vezina Trophies (best goalie), the Calder Trophy (best rookie), and the Conn-Smythe Trophy (most valuable player in the Stanley Cup Playoffs), which he actually won the year before he won the Calder. To put it in context, imagine Andre Vasilevskiy retiring after 2021’s Cup win, his second, at age 26. It just doesn’t happen.

It wasn’t the first time Dryden had done the unexpected. After winning the Stanley Cup in his first post-season appearance in 1971 (the year he won the Conn Smythe Trophy), Dryden, unable to negotiate a contract to his liking, sat out the entire 1973-74 season, opting instead to finish his law degree. (Dryden had earned his undergraduate degree from Cornell University, where he led the Big Red to an NCAA hockey championship in 1967.)

The Dryden we meet when the book opens seems tired and maybe a bit jaded.

I also thought about me: a little wearied, a little worn, tormented by doubts and feelings and lifelong illusions I can no longer reconcile, yet still able to find joy in the game. It’s a different game from the one I played on a driveway twenty five years ago, grown cluttered and complicated by the life around it, but guileless at its core and still recoverable from time to time.

The book takes us through each day of the week, Dryden mixing the narrative of what’s happening with the team in real-time with memories of other epochs in his life, and with ruminations on the game itself. We meet an incredible cast of characters: the Canadiens inscrutable and stodgy manager Scotty Bowman, outspoken defenseman Guy Lapointe, prolific goal scorer Guy Lafleur, among others, many of whom would later join Dryden in the Hockey Hall of Fame. We experience life behind the scenes of an NHL team that has grown complacent with its success, and despite its talent, is having trouble finding the motivation to win.

Related: Canadiens’ Ken Dryden – Truly One of a Kind

The city of Montreal and the Montreal Forum are also so well-drawn they are almost characters in and of themselves. Dryden, a Toronto native, explores his feelings toward French Canada and his adopted city, seeming at times like a stranger in a strange land.

Dryden on Soviet Hockey, Violence in the Game, and More

But it is when Dryden waxes philosophical that The Game truly shines. There are protracted passages on how Soviet hockey forced Canadien hockey to reconcile with its own shortcoming:

The Soviets pass better than we do because their crisscross diagonal patterns allow it, and demand it; because passing is a fundamental of their game, fostered and encouraged by their leadership; because the instincts and skills necessary to it develop naturally from practice and use. We need no less.

Page 260

How the NHL allowed violence to evolve with the game after it had outlived its usefulness:

“The violence of our game is not so much the innate violence in us as the absence of intervention in our lives. We let a game follow its intuitive path, pretending to be powerless, then simply live with its results.” (p261)

And how the camaraderie and mutual goal of winning, strived for and achieved, even through his cynicism about the game, still means something:

“It’s quiet. The music has stopped. For some, the weekend is over. They gather up cigarettes and coats, say perfunctory goodbyes; at a table at the back, no one moves. It is our time. The luckless climb from their barstools; more tables are pieced together. Jackets get slung into chairs, ties loosen, talk comes dressing room-easy. It’s about goals and goals missed, money, women, cars, golf. Anything. Stories that we’ve heard before, and some we haven’t; and will again. It’s my favorite time, when something is done and over, and good, when there’s nothing more to do, and no place to go until morning. Everything slows down. Words get softer. We speak of “the game” this, “the game” that. Sentences trail off, never finished. Things go unsaid. Yet we nod and understand. It is at moments like this that I remember why I play.”

The 30th Anniversary Edition includes epilogues from both 2003 and 2013, the latter of which is especially moving. The tradition of letting players on a Stanley Cup championship team have a day with the Cup didn’t begin until 1995, many years after the author had been out of the sport. But Dryden manages to convince te Hockey Hall of Fame CEO Jeff Denomme to allow him his day with the Cup in 2011.

Dryden brings the Cup to Domain, a small town in Western Canada and the birthplace of his father; and to Toronto to be enjoyed by the members his youth hockey team (Etobicoke Indians), and the neighborhood kids who played hockey in his driveway. The passages are sure to bring a smile to any hockey’s fan face.

Dryden, who would later serve as a member of the Canadian Parliament and a member of the Cabinet, is more skilled than your average sportswriter. The overall tone of the book is one of erudition and introspection and is a must-read for not only any fan of hockey but for any fan of sports.