After decades of failed playoff runs, miserable ownership and a dwindling fan base, the Chicago Blackhawks didn’t just built a champion. They built the embodiment of what the model NHL franchise is in the 21st century.

When you take into account the limitations the salary cap has put on NHL teams since the 2005 lockout, the Blackhawks certainly are the closest thing to a dynasty. Until another team finds a way to top their achievements in the coming years, it will be more than difficult to argue against putting Chicago’s three Stanley Cups in six years with the many great runs in NHL history. For now, though, let’s reflect on how this franchise was able to win what probably is their most difficult championship.

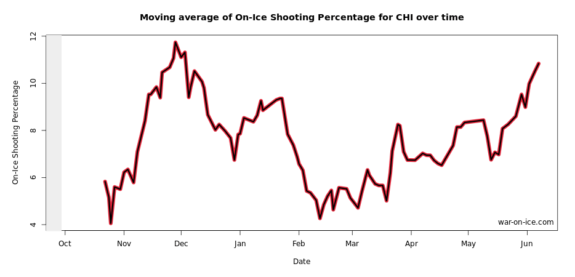

When the regular season was over, the Blackhawks completed a year where, despite being the best score-adjusted puck possession team not named Los Angeles, also had one of the worst shooting percentages at even strength. Most of that was due to a propensity of throwing the puck at all corners of the offensive zone rather than crashing the net and attacking the high percentage areas. This resulted in some below average seasons to some of their key offensive areas, with Patrick Sharp and Patrick Kane topping the list. It also resulted in Chicago sitting in third place in the most difficult division in the NHL, the Central Division.

Even with a goaltender change, the Blackhawks were fortunate that the puck luck went in their favour in their first two series against Nashville and Minnesota. When they had to face Anaheim, however, Chicago faced their toughest challenge yet. The Ducks were a team that improved more than any team in the NHL at the trade deadline by upgrading their blueline and group of checking forwards. Despite that, offense was the name of the game during this seven game series. In the Western Conference Finals, the Ducks and Blackhawks scored a whopping 46 goals and averaged a combined 115.6 score-adjusted shot attempts per 60 minutes at even strength. Even when Chicago finally obliterated Anaheim in game seven, 5-3, they came into the Stanley Cup Final showing chinks in their armor.

The Final

As mentioned in my Stanley Cup Final preview, every one of head coach Joel Quenneville’s teams since he has been in the Windy City have finished in the top-ten in shot suppression coming into this season. This year, the Blackhawks finished 11th and the had a blue line that was clearly in decline. During the offseason, Nick Leddy was traded to the New York Islanders for cap relief. Michal Roszival and Johnny Oduya were not getting any younger and trade acquisition Kimmo Timonen became an absolute hindrance from a puck possession standpoint on the third pairing.

When the Stanley Cup Final arrived, Quenneville lost Roszival to injury and Timonen was benched for replacement-level defensemen David Rundblad, Trevor Van Riemsdyk and Kyle Cumiskey. Also, there seemed to be a weird distrust by Quenneville for Kris Versteeg, who had a strong season supporting the team’s scoring lines. Instead of Versteeg, Quenneville decided to go with Bryan Bickell, who has always been a reliable checking line forward, but is now a bad fit for the current iteration of a Blackhawks team that has two scoring lines and the best two-way top line in hockey lead by Jonathan Toews and Marian Hossa. Bickell and his $4 million cap hit was never going to look good on the fourth line, and with newly-acquired Andrew Desjardins in his usual spot there, there was nowhere he could fit in the lineup.

After three games, Tampa began to develop a third line that could rival Chicago’s. They began to use it well by taking advantage of easy assignments, and then freeing up their top six forwards to roam free and score goals. With the Lightning going up two games to one and stealing Anaheim’s playbook of putting higher quality shots instead of quantity, Quenneville needed to make adjustments again.

Rising star forward Brandon Saad was moved from the top line to the second line. Versteeg, who finally received playing time during the finals, was moved to the third line and the struggling Sharp was moved up to the top line. Even if these were lines that visually made sense, data and possession stats will tell you that there is too small of a sample size to trust that these three lines would have worked. A top line of Toews, Hossa and Sharp could work with 62% of the shot attempts going in their favor in over 117 minutes of ice time together, but that’s still considered a small data set for a duration of an NHL regular season. Meanwhile, a line consisting of Kane, Brad Richards and Saad only played nine total minutes together while a Versteeg, Antoine Vermette, Teuvo Teravainen line only played one minute and five seconds together and were out-attempted 4-0.

What happened though, despite its early warts, was the start of Chicago’s run to the championship. With their famous second line already being shut down by Chicago’s top pairing, Tampa needed to find offense from somewhere else. They couldn’t and the Blackhawks were able to limit the Lightning to less than 50 shot attempts per 60 minutes in a tight-checking game four. In game five, Chicago opened up their offense with over 33 scoring chances, 13 high danger zone shot attempts and 58 total shot attempts in 55.1 even strength minutes while score-adjusted. Numbers like that reminded everyone how explosive Chicago can be when things click. The best way to do that, as always, is making sure both Toews and Kane would be given the best teammates and zone starts possible. By game six, Kane had his centerman help him set up passes that would clinch the series and championship.

It was just last summer that Brad Richards signed for only one year and $2 million. Yes, his reputation was damaged (though unfairly) by his contract being bought out by the New York Rangers, but any other team could have had him for a bigger deal. Instead, Richards took a discount to play for a champion and little did he know that he would be among the biggest reasons for that. He would go on to have two assists and a team-high shot attempt plus-minus of +7 at even strength after the Blackhawks settled down after a nervy start. After being out-attempted 23-14 in the first 30 minutes of Monday’s clincher, Chicago went on an eight minute barrage that was finished off by Duncan Keith’s tally to make it 1-0. During that sequence, the Blackhawks doubled their shot attempt count and would turn that category into a 50-50 battle the rest of the game.

It also was dead even in shot attempts the whole series and the goal totals certainly reflected that. Overall, only 23 goals were scored in six games with Chicago only scoring 13 of them. But what made Chicago go from a 2-1 hole into winning three games in a row was how they were able to turn the tables in the shot quality battle. In games one through three, Tampa averaged more score-adjusted scoring chances per 60 minutes and score-adjusted high danger zone shot attempts per 60 minutes at even strength, 25.2-20.5 and 10.8-6.9, respectively. In the rest of the series, Chicago turned those numbers around and spat them at Tampa Bay’s face 26.3-22.3 and 11.4-8.0. Most importantly, Tampa’s percentage of shot attempts blocked went from 23.5% in the first three games to 36.8% in the final three. It can’t be stated enough how much of a gamble Quenneville pulled off with his line combinations, but like his general manager Stan Bowman has done during his five year reign, most of them pay off.

So What Now?

After all the fun and games, too many players on this team will become free agents and may no longer call the United Center home because of how tight Chicago is up against the salary cap. Vermette, Richards, Desjardins seem to be off to the open market, hoping to get one last big payday as will Roszival and fellow defenseman Johnny Oduya. Brandon Saad will be asking for a major raise, as will Marcus Kruger and many others. Either way, this team will be different next year and, despite the recent signing of KHL star Artemy Panarin, it will be a struggle to see how the Blackhawks can swim easier in that bloodbath of a Central Division as they did in the playoffs this year.

Surely though, they won’t care right now. The most memorable of all the departures, clearly, is Kimmo Timonen. After 1,108 regular season games, five olympics and two cup finals appearances, the 40-year old defenseman officially rode into the sunset and walked away a champion. It’s moments like these where you can complain all you want about him being in decline and only playing such an insignificant part on a cup team. But like Quenneville on small sample sizes, Bowman on salary cap restrictions and Timonen and the rest of his teammates about what will happen next year, they won’t care. They did it their way and their way works more than anybody else, because nobody likes winning more than they do.