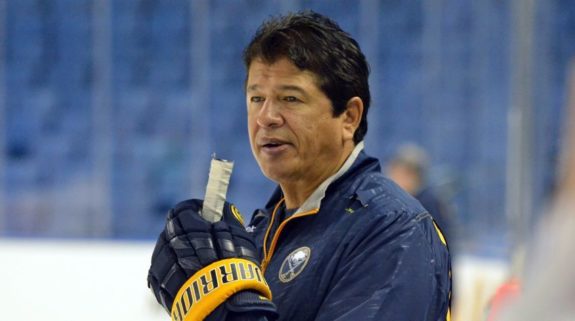

The sun was shining, and spring had settled in on the southern Ontario city of St. Catherines the day Ted Nolan sat down to share his thoughts with The Hockey Writers. Still, dark clouds continued to hover over his last go-around as head coach of the Buffalo Sabres.

“When I was there, they wanted that first-round pick so bad they didn’t care about winning. It proves to you just how difficult winning really is. Now they want to win, and they can’t seem to find a way,” Nolan said.

The 2014-15 season is known as “the tank year” among fans and followers, and the mere mention of those months brings up a mound of painful memories for Nolan. After all, he’s a competitive, proud human being who vehemently hates to lose.

“It was probably one of the most difficult years I ever had in sports in my entire life,” he told THW. “The players will never tank. That’s one thing I know about players. They would never tank on purpose or want to. But sometimes, the organization puts the team in a tough spot where it’s extremely tough to win and compete, and that’s exactly what (Tim) Murray did when he was general manager. They wanted to get that first overall pick so bad that all their thinking was: how many games do we have to lose to get that, which I thought was a very bad thing to do.”

The Sabres finished dead last in the league that year with a 23-51-8 record and 54 points. At the draft lottery, the balls did not drop in their favor — they missed on the first overall pick, Connor McDavid. However, the Sabres ended up with a pretty good consolation prize in Jack Eichel.

Nolan was fired before Eichel ever played a game.

An Everchanging Roster Made Success Hard

When Nolan came in as coach, he later brought along ex-National Hockey League goaltender Arturs Irbe for his goaltenders. Irbe had been working with him in Latvia, with the men’s national team. He felt with the job security of a three-year extension, there was room to grow with the Sabres.

Nolan filled out his staff with guys he trusted, like Bryan Trottier, Danny Flynn and Tom Coolen. Still, at times it seemed even if he had some of the greatest minds in all of sports on his team — from Scotty Bowman to Vince Lombardi — winning would still be impossible that year in Buffalo.

Nolan told THW that there were many obstacles to success that he couldn’t overcome.

“(Murray would) shorten the bench and be putting a lot of young kids in positions (where they couldn’t have success). Sometimes you want to get your young players in, obviously, but you also have to develop properly and give them time in the minors,” Nolan said.

That’s a philosophy that many of the greatest hockey minds, like New York Islanders general manager Lou Lamoriello, live by, and Nolan does as well.

“A lot of these kids come from junior where they’re living with billets and 18 or 19-years-old, into a professional hockey league, and you’re playing with men who are 30-years-old with beards and married with kids. Going from one environment to the other. It’s a change and if you haven’t got proper structure. I tell you, it’s tough, and a lot of them either make it or break it. Development is so important. Bringing in people when they’re ready. Physically and mentally.”

Nolan felt the organization left goaltending exposed throughout the “tank year.” Five goalies suited up for the Sabres in the 2014-15 season, three of which had minimal NHL experience.

“We did rush our goaltenders. One of them (would) play very well, and he’d be traded within a couple of days,” he said. And it was the same with all positions.

“We had a lot of rotation and no stability, so it was extremely tough to get that camaraderie amongst the team because it was changed all the time.”

Nolan and Murray Didn’t See Eye-to-Eye

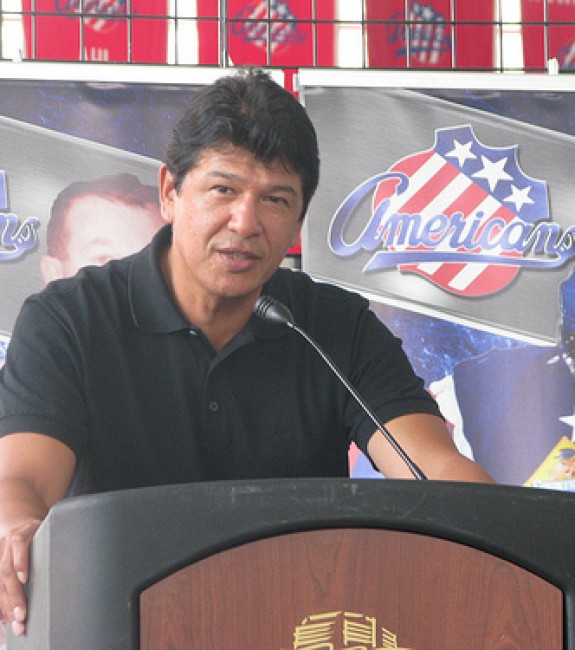

On Nov. 13, 2013, Nolan took on the job as interim head coach on a Sabres team in jeopardy. That day, in what has become a familiarly sore scene for Sabres fans, owner Terry Pegula took his place at a podium for a news conference to announce sweeping changes to the organization.

The firing of general manager Darcy Regier and head coach Ron Rolston marked the beginning of a short stint as president of hockey operations for former Sabres’ captain Pat LaFontaine. He turned to Nolan, his old coach and friend, to take over the bench.

Four months later, after Murray’s Jan. 9, 2014 hiring as general manager and LaFontaine’s swift departure — under circumstances that later required a non-disclosure agreement — Nolan was handed the full-time coaching gig and given a three-year contract extension through to 2017.

Several things happened that season that spoiled Nolan and Murray’s relationship to a point where he was relieved of his duties shortly after the trade deadline on Apr. 12, 2015. According to Joe Yerdon, writing for NHL.com, the coach and the new GM didn’t exactly see eye-to-eye.

“It was never about that he wasn’t my guy,” Murray said about the bench boss he had inherited when he took over.

“I take a lot of the blame,” he added. “We didn’t have a great relationship. We had a decent relationship. We didn’t hate each other. We spoke. But going back to player personnel decisions — going back to him not being consulted on the trade deadline — those are things that I think are normal that maybe somebody else doesn’t think are normal. My normal and somebody else’s normal isn’t the same, and I understand that.”

Murray said he was keen on the idea of keeping a lot of the players the team had that year, but by the time the deadline approached, he had changed his mind.

“Certainly after the trade deadline, trading out guys, I had a big part in that, there’s no question, and I own that,” he said. “But up to the trade deadline, I was open to keeping guys, I was open to maybe discussing contracts with guys that were coming due, but the place we were in was the place we were in.”

Murray Trade Tracker

The teardown truly began in 2014, only a few months into Nolan’s tenure. The following is a chronicle of Murray’s moves during that time.

- Almost as soon as he was hired, Murray got to work trading Ryan Miller and Steve Ott to the St. Louis Blues in exchange for Jaroslav Halak, Chris Stewart, William Carrier, a first-round pick in 2015 (dealt to the Winnipeg Jets, who chose Jack Roslovic) and a conditional third-round pick in 2016 (Linus Nassen) on Feb. 28.

- Five days later, at the 2014 trade deadline, he moved Brayden McNabb, Jonathan Parker, a second-round pick in 2014 (Alex Lintuniemi) and another second-round pick in 2015 (Erik Cernak) to the Los Angeles Kings for Nicolas Deslauriers and Hudson Fasching, then flipped Jaroslav Halak and a third-round pick (Robin Kovacs) to Washington in favor of Michal Neuvirth and Rostislav Klesla.

- That same day, he whisked Matt Moulson and Cody McCormick out of town to Minnesota in exchange for Torrey Mitchell and two second-round picks (one of which was traded to the Washington Capitals who selected Vitek Vanecek in 2014, and the other ended up as Chicago Blackhawks’ Chad Krys in 2016).

- In February of 2015, Murray shipped Tyler Myers, Drew Stafford, Brendan Lemieux, Joel Armia and the 2015 pick that ended up being Roslovic to the Jets in exchange for Evander Kane, Zach Bogosian and Jason Kasdorf. That same day, he traded goaltender Jonas Enroth to the Dallas Stars in exchange for Anders Lindback and a conditional third-round pick in 2016 (Casey Fitzgerald).

- At the 2015 trade deadline, Murray moved forwards Torrey Mitchell and Brian Flynn to the Montreal Canadiens, traded goalie Michal Neuvirth to the New York Islanders for goalie Chad Johnson and moved Chris Stewart to the Minnesota Wild for a second-round pick (Vojtech Budik).

During all this shuffling, players like Johan Larsson, Philip Varone and Mikhail Grigorenko from the Rochester Americans joined a revolving cast of others that filtered in through the lineup like rain into a paper cup.

In 2017, Murray’s fate matched Nolans. He was also fired. He claimed he wanted to do a rebuild quickly. But his gambles didn’t pay off. The team continued to spiral around in mediocrity.

Nolan Still Loves the City of Buffalo

Nolan still follows the Sabres to this day. The team and the city hold a special place for him, and it’s a miracle that those two dastardly seasons didn’t entirely tarnish the feeling.

“I hate to say it, but I follow the Buffalo Sabres a lot,” Nolan said. “Even when I was let go the first time, I was a big Buffalo fan. I worked for them. I really enjoyed my time. I fell in love with the people of Buffalo.

“I think Buffalo is a hard-working town and their fans are very compassionate about their sports club and if you can’t get motivated in that environment, maybe these athletes are in the wrong line of work.”

The excitement around hockey in that area of Western New York makes it feel almost like a Canadian city, and that struck him hard when he joined the club for the first time coaching through the 1995-97 seasons.

But the story of that first round with the Sabres also had a bitter ending. Relations became strained between the GM of the day, Jon Muckler and Nolan.

It began when star centerman LaFontaine was injured, and Muckler gave Nolan a direct order to continue dressing the Sabres star player. Despite returning for seven games after a hit from Pittsburgh Penguins defenseman Francois Leroux, concerns about the captain’s health kept Nolan from wanting him to play.

LaFontaine later admitted in a TSN feature on Nolan, ‘The Unwanted Visitor’ from January of this year, that he confided in his coach that something wasn’t right. He would end his career in 1998 because of head injuries. (from ‘HOCKEY; LaFontaine Leaves the Game Reluctantly,’ New York Times, 08/12/1998)

In his last year of that first stint with the Sabres, Nolan won the Jack Adams trophy as the league’s best coach. But soon after, with his contract expired, new general manager Reiger was given the option to hire his own bench boss. He didn’t fire Nolan and instead decided to offer him an insulting one-year deal.

In footage that aired with The Unwanted Visitor documentary, former Sabres vice-chairman Bob Swados told TSN in 2005 the original discussions were to make an offer that Nolan would reject.

That’s exactly what he did. He wouldn’t coach again for ten years.

But he still followed the team from his home near Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

“(Buffalo) took me in as one of their own when I was there the first time. So I had a special place in my heart for the city when I was let go, and even though I wasn’t coaching for about ten years, I was still watching what was going on with them.”

It’s the same story now, he said. “I watch them, and the people of Buffalo really deserve a winning team, so hopefully, they’ll find their way and get through this stuff.”

According to the TSN feature, Nolan was so upset after winning the Jack Adams Award that he threw the trophy down the stairs and broke it in several places. “It didn’t mean much to me because if it meant much, I’d still be working in the game,” he told the network.

The second time around with the Sabres ended with just as much consternation but perhaps more lasting scars to his career as a coach and his health.

Tanking Was Bad for Nolan’s Health

Just showing up to the rink every day and finding ways to motivate yourself when the team’s goal is to lose games was more than enough to start causing Nolan physical pain, he told THW.

“I was physically ill for sure,” he said. “I love to compete, and I love to win, and when you’re unable to do it, it just makes you physically ill… because (they) wanted to lose so badly. I’ve never been in a situation like that in my entire life…I went up to about 210/215 pounds, I think, and I’m currently 180. I had never been that heavy before. I had trouble sleeping. It just wasn’t a very good spot to be in.”

It wasn’t that he was trying his best, and it just wasn’t working. Nolan said he was trying his best, and management’s moves worked against him.

“I could sleep with the best of them if I went to work knowing that we gave our best and we had a chance to compete. And when you don’t put a good team forward, and you put some of the people that you have in jeopardy as far as coaching wise and not surrounding them with proper leadership, it’s very, very difficult, so it was a tough year, and I was glad it was over. But the one thing I know I don’t like to do is I don’t like to lose.”

With the current Sabres fortunes not being much better, Nolan says he suffers with them.

“It’s painful to watch,” he said with a sigh. “Hopefully, they get it on the right tracks.

“I joke… but maybe they’re tanking again,” he said.

Nolan’s Main Focus Now Is on Youth

Despite two turns at the wheel with the Sabres that both ended terribly — leaving him with a sour taste in his mouth that lasts to this day — Nolan’s love for the game never died down.

He was born and raised on the Garden River First Nation. Since the end of his playing career in 1986, he has made public speaking appearances to motivate kids living on First Nations reserves throughout Canada to follow their dreams.

He and his two sons Brandon and three-time Stanley Cup champion Jordan run hockey schools on reserves through their company, 3 Nolans. The crew even counted current Sabres defenseman Brandon Montour, as one of their instructors during sessions held in Paris, Ontario, within the Six Nations of the Grand River and about a 14-minute drive from Brantford.

“This is my true passion,” Nolan said. “Growing up in one of our communities and not having too much when I was a kid and not having a chance to play AAA hockey… I really wanted to come back and share some of the stories and how to get over some of those obstacles, how to face some kind of adversity that we as First Nations face and how to close one ear and don’t hear the racism as much. A lot of the kids that I played against growing up were maybe two or three times better than I was, but unfortunately, things didn’t work out.”

Nolan says he can remember occurrences, working his way up through the ranks to becoming a pro, of being called a “drunk” or told to “get back to the reserve.” It meant that when he was coaching, he formed special bonds with First Nations players, like in junior hockey with guys like Chris Simon, Denny Lambert and Gary Roach.

“A lot of us, we went through the name-calling and the prejudice — you had to be pretty tough,” he said.

Nolan Believes He Can Still Coach

Nolan’s work with kids and First Nations communities is interrupted now and again by the NHL, but he always returns to it when those commitments have passed. It’s what keeps him going. But he hasn’t given up the dream of coaching in the league and believes strongly that he can still do it.

“I would coach in a second. Just, unfortunately, my phone is not ringing off the hook,” he told THW. “I would love to coach, and I think I can coach.”

In the Canadian Hockey League, he took the OHL’s Soo GreyHounds to three straight Memorial Cups, finally winning it all in 1993. He won a league championship with the QMJHL’s Moncton Wildcats in 2006. He was coach of the year with the Sabres in 1997. In Latvia, he took a scrappy group of young kids to the 2014 Sochi Olympics’ quarter-finals, where they lost a close match, 2-1, to a powerhouse Team Canada.

Still, whenever a job opens up in the NHL, his name is passed over. He believes his reputation has been tarnished to the point that no one attempts to get to know him. He admitted on The Unwanted Visitor that he thinks this is partly because of systemic racism within the NHL.

“People have an assumption, or they think they know what a person is like, and they never even talk to them,” he told THW. “I never talked to anybody in sport all year, and they thought I was a GM killer, and some of the rumors that were out there were just disgusting,” he said. “I think my record can prove that I can coach. I just have to be with an organization that wants to win.”

That certainly wasn’t the case when Nolan last leaned on his knee behind the players. And guys like LaFontaine claim they will “go through a wall” for him. Twice, strained relations with general managers turned Nolan’s fortunes on their head. If there is a next time, perhaps he will be given a real shot at success.