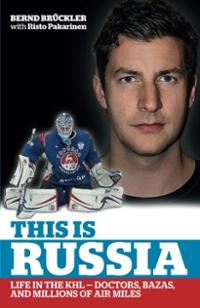

This is Russia: Life in the KHL – Doctors, bazas and millions of air miles by Bernd Bruckler with Risto Pakarinen (December 6, 2013, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. Paperback. ISBN 9781494379285)

Austrian goaltender Bernd Bruckler did not grow up in a hockey thriving country. While his friends were out playing popular sports such as skiing and soccer, Bruckler wanted to stray from the rest and try something new — hockey. His parents made him dedicate his time to the game, which ended up paving his way to the professional level. As a young boy emerging as a teen, Bruckler had to skip all the fun activities such as partying because his focus was on success.

Austrian goaltender Bernd Bruckler did not grow up in a hockey thriving country. While his friends were out playing popular sports such as skiing and soccer, Bruckler wanted to stray from the rest and try something new — hockey. His parents made him dedicate his time to the game, which ended up paving his way to the professional level. As a young boy emerging as a teen, Bruckler had to skip all the fun activities such as partying because his focus was on success.

In the first few chapters, the book covers the difficulties Bruckler and European hockey players have in trying to play in better junior leagues in North America due to import restrictions. The Graz, Austria native had to try out for several teams before landing in the United States Hockey League with the Tri-City Storm. After one season in the USHL, Bruckler received offers from several big-name hockey universities, but committed to the University of Wisconsin on his first college visit.

While the book does detail much more of his early hockey career in detail, although interesting, the meat of the book lies during his time in the Kontinental Hockey League (KHL) with Torpedo Nizhny Novgorod and Sibir Novosibirsk. While with his wife in Russia, Bruckler experienced things he was appalled by in Russian society. Whenever he questioned why something was a certain way, the common answer seemed to simply be, “this is Russia”. Garbage can be found on the sides of roads and highways, unfinished interiors of buildings, and many more Russian stereotypes are made true.

Although Russia is no longer a communist country, they still try and outdo North American lifestyle. Russian President and hockey fanatic Vladimir Putin wanted to compete with the NHL in the United States and Canada by establishing the KHL in Russia and the surrounding countries that were once part of the Soviet Union. In some ways, the Cold War still continues in our midst.

In chapter 6 titled “Money makes the world go ’round”, Bruckler details the shady money handling not only throughout Russia, but throughout the KHL, as well. Owners of large businesses, and friends of Putin, would own teams in the league. Players essentially worked for the company, rather than the club, and would receive paychecks from the particular business. Below, Bruckler described one shady experience when Torpedo received their paychecks late.

After practice, the players were told to wait for their turn to get paid. There was a big guard in front of one of the storage rooms. He was, naturally, dressed in black. After a while, they called me in.

I grabbed a garbage bag and walked into the room. There were two more guards inside, and a lady behind a desk, and in front of her were wads of money, some in little plastic bags, some bound with rubber bands. Under each pile there was a note with the player’s name, so I could see where it said “Bruckler”.

During the time of the Soviet Union, the national hockey team would reside in bazas with the military for most of the year, without contact with their family or friends. Focus was the intention, but comfort was a lacking essential. Now-a-days in Russia, the idea still remains, but in a lesser magnitude. Bruckler and his Torpedo teammates would be forced to reside in the team’s baza the night before games and during training camp. Below is a description of the baza from the book.

To say that the Torpedo baza was “in the middle of nowhere” is not a figure of speech. I dare you to try to find it on Google Maps. There may be street maps of Nizhny for sale these days, but the Torpedo baza won’t be on it.

It was an old, two-storey red-brick building some 40 kilometers, or 45 minutes by car, from the city in the middle of the forest, a good five kilometers off the highway on a back road. In regular Nizhny traffic, it was an hour and fifteen minutes’ drive from the arena.

That place was built to be a baza. Outside, there was old equipment for off-ice training, and it looked like equipment the military would use. There were car tires to jump in and out of, ropes for circuit training.

Bruckler and Swedish teammate Joakim Lindstrom would sneak out at night and sleep at home the night before their games. The effect? A better performance on the ice. Bruckler ponders about how great USSR star players like Vladislav Tretiak, Valeri Kharlamov and Sergei Makarov could have been if they were sleeping in their own beds at night in a comfortable environment.

Another difficulty many do not realize is the travel for the teams along the Pacific ocean in the Eastern Conference. Bruckler played for Sibir Novosibirsk located just north of Kazakhstan — a 3 hr 45 min plane ride to the capital city of Moscow. He detailed the difficulties with travel whether it was traffic (via bus or car) or questionable safety on planes. The team often used the same plane model, Yak-42, that went down with the Lokomotiv Yaroslavl team inside. That certainly raised hairs whenever stepping onto the Yak-42.

This Is Russia: Life In The KHL is an outstanding read for anyone intrigued about life in Russia and the untold stories of the KHL. Even for those who do not like reading, including myself, found this book easy to sit down and read without getting bored or dozing off.

Comments are closed.