Before the era of massive contracts and multi-million dollar stars, the greatest players in the National Hockey League needed to supplement their income with an offseason career. At the time, the league was still considered a fledgling organization and lagged behind its North American contemporaries in both popularity and revenues. While professional hockey is now a full-time gig, the legendary players of decades past spent their offseason working full time.

Maurice Richard

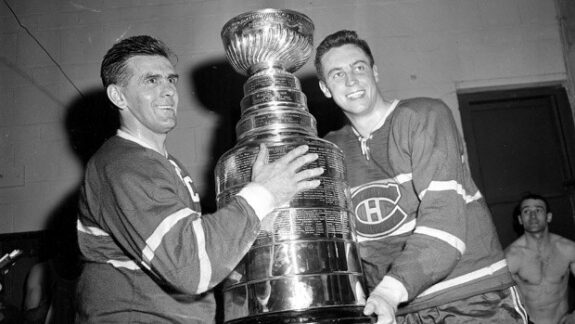

While it may seem strange that the greatest player in the history of the Montréal Canadiens, the first player to score fifty goals in a single season, and the captain who began the first Canadiens dynasty and won eight Stanley Cups with Les Glorieux would require a second job, the era necessitated he get one. Maurice Richard began working for the Canadian Pacific Railway in 1937 at age 16 and continued to do so even as he set numerous NHL records and became the ambassador for the Canadiens.

There was history behind Richard’s association with the CPR. His father, Onésime, worked as a carpenter with the railway intermittently in the early part of the 20th century. The Rocket worked offseasons in a railcar construction warehouse in what is now Montréal’s Angus Shops district, a facility responsible for producing locomotives and passenger and freight cars.

Bobby Hull

The “Golden Jet” was most well-known for his years with the Chicago Black Hawks in which time he became one of the game’s greatest-ever scorers and among the few players to sport the No. 9 alongside other greats like Gordie Howe, Richard, and Johnny Bucyk. A prolific scorer with five seasons scoring 50 or more goals, his speed and puck handling ability turned him into a legend in two leagues.

Like many of his contemporaries, Hull worked during the offseason and supplemented his income during the season as well. Despite his gap-toothed grin, he had a reputation as one of the most attractive players in the game. Capitalizing on this, he found work as a model. He appeared on television as a spokesman for Vitalis hair tonic and in magazine pages as the poster boy for swimsuits, sweaters and socks (“Bobby Hull” by Trent Frayne. Maclean’s Magazine, 22nd January 1966).

Trent Frayne of Maclean’s Magazine described images of a man whose attractiveness was almost inhuman; Frayne saw “his tawny pelt glistening in muscles piled on muscles, grinning down on a doll wearing a delicious dispersement of skin” (Ibid). Makes sense, then.

Derek Sanderson

Derek “Turk” Sanderson was best known for his time with the Boston Bruins in the late 60s and early 70s and for providing the assist on what many believe to be the greatest goal in NHL history, Bobby Orr’s overtime tally against the St. Louis Blues in the 1970 Stanley Cup Final.

Scoring north of 20 goals and 20 assists in almost all of his seasons with the Bruins, he seemed like a staple of the team and in the league. Sanderson’s career, unfortunately, fizzled after the 1971-72 season, and he made the jump to the Philadelphia Blazers of the World Hockey Association. Signing the most lucrative contract in hockey history to that point, he never got the chance to prove his worth, as injuries limited him to only eight games in 1972-73. He would eventually find his form again with the New York Rangers in 1974-75, scoring 25 goals and registering 25 assists.

Needing to supplement his income during the seasons in which he was out for long periods, he partnered with football legend Joe Namath and opened a New York City nightclub called “Bachelors III.” What began as a responsible investment quickly turned sour, as the reputation of the club began to decline and Sanderson was forced to withdraw his stake in the venture.

The era of the seemingly underpaid hockey player is largely forgotten; the era in which the greatest players in the world finished the season, went home and went to work like everyone else. The fact that the greatest players of the day got up each morning and went to work alongside average citizens endeared them further to the fans and helped in a small way to turn many of them into the legends of the game we revere today.