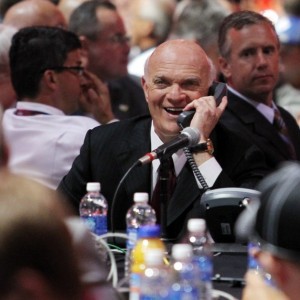

For years Lou Lamoriello and the New Jersey Devils were the smart kid sitting in the back of the classroom. Tightly budgeted, strict rules regarding among many things, facial hair. They were the third team in the New York market, sliding into the corner column of even New Jersey-based publications. Though if headlines on the team were scarce in the regular season, they were regulars in June for a team that had no shortage of success–three cups, 21 playoff appearances–five cup appearances to be exact. His arrival to Toronto was made official on Thursday, July 23, moments after resigning from the Devils after a storied tenure that lasted nearly three decades. For the Devils, it’s a continued reminder that the days of trap hockey, Martin Brodeur and playing across the street from Giants Stadium are over. They’re no longer the kid in the back of the classroom, hiding all the right answers. That kid, who will turn 72 in October, has gone on to Toronto–trying to bring experience and some old tricks to a place that isn’t New Jersey, by any means.

In his 28 years at the helm of the Devils, Lamoriello developed a reputation as a punctual, thorough and crafty GM who rarely blinked in contract holdouts, wasn’t afraid to make a change behind the bench or on the ice–even with just games left in the regular season and was the master of team-oriented hockey. That meant sacrifices of big and small proportions.

What made a 15-year deal for Ilya Kovalchuk so shocking around hockey was that Lamoriello had OK-ed it. It went against type. It went against the philosophy that earned three championship banners in the rafters. And yet, when Kovalchuk balked to Russia, the departure came as a huge loss to the Devils. He, like many others found solace in the structure and committed himself to the norms of New Jersey–like passing to a teammate on an empty net, or killing penalties with the same enthusiasm as playing the point on a power play. Perhaps that is the most underrated part of the Lamoriello’s excellence and legacy: players buying into the system, and on multiple occasions returning for more.

It wasn’t uncommon for coaches and players to return to the organization, even if that meant making a trip to the barber before arriving to work. Lamoriello sent players packing if they questioned the team’s direction or philosophy–a notion that’s drawn comparing a former Providence, R.I., math teacher to fictitious New Jersy mob boss, Tony Soprano. Lamoriello was indeed the boss, one who treated his players with respect, but demanded accountability and adherence to the plan, that meant less money and point totals. For all the frustrations of playing in New Jersey–players stayed loyal. Winning helped, unparalleled structure to anything in professional sports was another part of it. Players who worked under Lamoriello were protected and if that bothered the media–take a number. The outside noises in N.J.–contract disputes, changes in ownership, financial issues, lawsuits with Newark–it was all irrelevant. The only thing that was important was the day-to-day operations on the ice.

Lamoriello won’t be short distractions in Toronto, nor will he be heading into a media market that gets any easier. The usually secretive Lamoriello, who was known to nix deals if the press or anyone else leaked it will have a lot more hiding to do, but if Lou insulates his staff and players the same way he did in New Jersey, there’s little who doubt he can’t do the same with the Maple Leafs.

While the hire was somewhat shocking, its logic begins to make more sense. Brendan Shanahan, a 1987 draft pick of Lamoriello in New Jersey knew his team had some pain ahead–new head coach Mike Babcock knew the same. The team has struggled with its identity, with its leadership and with its ability to chase the ultimate goal. In the latest hiring the team welcomes someone with experience in developing an identity and culture as well as a pedigree of success despite having limited financial resources. The latter won’t be an issue with a strong ownership group and the richest team in the NHL. Every tool a general manager could need or want will be available, Shanahan is trusting that Lamoriello is the best person to hand over the toolbox to and build a foundation that can sustain success for a long time.

Other GM’s have emerged over the last decade and change and the smart kid in the back of the classroom has been competing with both minds he’s mentored and those who have other unique experiences in a multitude of hockey environments–some with budgets, others with relatively none. What Lamoriello brings to Toronto is experience, obviously and he’s had perhaps one of the more unique resumes of a hockey executive.

In 1987 the Devils hired Lamoriello, a former athletic director, hockey coach and math teacher from Providence College to be the team’s president. Just prior to the start of the 1987-88 season, he named himself the team’s general manager. From there he made multiple strides in building an identity to a largely comical hockey franchise: He helped break the Iron Curtain of Soviet hockey players coming to the NHL as Slava Fetisov would leave Russia (with Lamoriello’s aid) and come to the United States to play for the Devils. Years later after star player-turned Leafs president, Brendan Shanahan signed an offer sheet with the Blues, the Devils were involved in an aggressive arbitration case to settle the compensation. The end decision: Scott Stevens, the team’s captain for all three cup championships. In 1990 a goaltender named Trevor Kidd was the talk of the draft, Lamoriello traded down though, deciding instead to take a chance on Martin Brodeur–and the rest is history.

The three-year deal isn’t bringing three consecutive cups to Toronto, but for a team looking to build an environment and winning culture this is a good start. Shortcuts, ‘salute-gate’ and selfishness won’t be tolerated. The message and philosophy in Toronto–the one that was the norm in New Jersey will travel to all levels, to all personnel. For the era that’s ended in New Jersey, a foundation still lingers. For Toronto, they hope they’ve found someone to build one.