During the 1970s, only the Montreal Canadiens and Boston Bruins had more victories than the Philadelphia Flyers’ 424. During that decade, the Flyers won back-to-back Stanley Cups in 1974 and 1975, went to two more Finals, and missed the playoffs once. Furthermore, they registered 100 or more points in five consecutive seasons between 1974 and 1978.

The Flyers of that era are often overlooked by the Bobby Orr-led Bruins and the Guy Lafleur-led Canadiens because the Flyers lacked the elite offensive threats that other teams had in Orr and Lefleur of the 1970s or Mike Bossy and Wayne Gretzky of the 1980s. Yet, a lack of big-name scorers on Philadelphia’s rosters during the 1970s didn’t hinder their success.

Related: Origins of Every Eastern Conference Team

Instead, they were led by “the Broad Street Bullies,” a group of players whose toughness and tenacity was unmatched, yet they weren’t exclusively goons. Rather, they brought an offensive punch, hit hard, regularly pushed the limits of the rulebook, and backed it all up with literal punches if the situation deemed them necessary.

The Flyers of the 1970s, and specifically the teams between 1973 and 1976 were three of the best rosters ever assembled. However, they’re often lost between the Bruins and Canadiens that succeeded at the same time and the New York Islanders and Edmonton Oilers that came after. Now, over 40 years later and no more Stanley Cups in franchise history, the Broad Street Bullies’ story remains as dynamic as ever.

The Flyers Before the Broad Street Bullies

Hockey in Philly Before the Flyers

Professional hockey in the City of Brotherly Love dates back to 1930 when the Pittsburgh Pirates moved cross-state and became the Philadelphia Quakers. They only lasted one season in Philadelphia with an abysmal 4-36-4 record and their .136 winning percentage remains second-lowest in league history. After the 1930-31 season, team owners announced they would not have a team the following season and the city had to wait 36 years before an NHL team returned.

Ed Snider Brings the Flyers

After the Quakers dissolved, the next rumors of an NHL team in Philadelphia arose in 1946 when a group attempted to raise money to build an arena and move the defunct Montreal Maroons south. However, they missed their deadline for funding and it wasn’t until 1964 that serious discussions to bring a team to Philly began again.

Those discussions were sparked by the late Ed Snider, then-vice president of the Philadelphia Eagles, who put forth a bid for an NHL franchise. Philadelphia was awarded the franchise for the 1967 Expansion over Baltimore and joined the league along with the California Seals, Los Angeles Kings, Minnesota North Stars, Pittsburgh Penguins, and St. Louis Blues.

The Flyers qualified for the postseason each of their first two seasons despite not having a winning record in either. In both playoffs, they were ousted by the bigger, stronger Blues in the first round. In 1968, they lost in seven games and were swept in 1969. The Blues pushed the Flyers around and dominated their smaller players. This led to Snider making the decision to change the team’s roster construction.

“…I don’t want to see our team ever get beat up again. I don’t give a (expletive) about this (team) having one policeman. Let’s have five or six.” Ed Snider after watching his Flyers lose Game Seven to the Blues in 1968, as told to The Hockey News.

The Plan to Get Bigger

The Flyers began implementing their plan to get bigger by drafting Dave “The Hammer” Schultz, Don Saleski, and Bob “Hound Dog” Kelly in the 1969 and 1970 Entry Drafts. Those three were the nucleus of what became the Broad Street Bullies with each player’s career penalty minutes double his point totals.

But it was the team’s decision to draft diminutive center Bobby Clarke in the second round of the 1969 Entry Draft that brought the group together and made them a legitimate threat to win a Stanley Cup. Yet, despite skilled and aggressive forwards, the Flyers wouldn’t have achieved their success had Bernie Parent not been in net as his 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons are widely considered the best consecutive seasons by a goaltender in league history.

Finally, no team would be complete without a fitting coach. Fred “The Fog” Shero was the man behind the bench for the Flyers’ Cup runs and although he wasn’t as aggressive as his players, he was a player’s coach and allowed their personalities to shine. These are the stories of those who made up the Broad Street Bullies and what allowed the Flyers to become one of the best teams of the 1970s.

GM Keith Allen

Keith Allen was the architect of the Broad Street Bullies and served as Philadelphia’s general manager from 1969 to 1983. He was also the franchise’s first head coach and guided them during their first two seasons with Bud Poile as general manager. Prior to becoming Philadelphia’s head coach for the 1967-68 season, Allen was a defenseman and played for the Detroit Red Wings in 1953-54 and 1954-55. He even had his name engraved on the Stanley Cup in 1954 after appearing in 10 games that season.

After his playing career ended, he coached the Seattle Americans/Totems of the Western Hockey League from 1956 to 1965 and left when the Flyers joined the NHL. He remained with them in some capacity until his death in 2014, serving as an executive following his tenure as general manager. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame as a builder in 1992, the Flyers Hall of Fame in 1989, and was named The Hockey News’ Executive of the Year for the 1979-80 season.

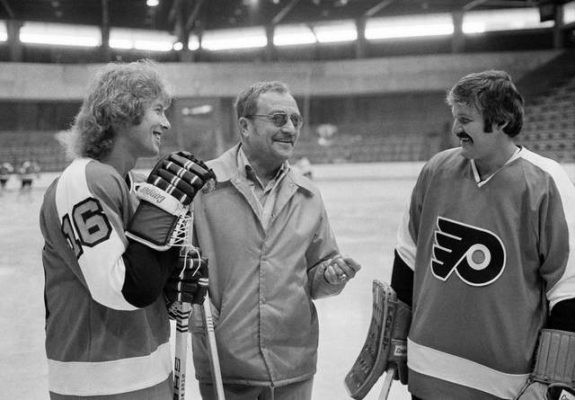

Head Coach Fred Shero

If Allen was the architect of the Broad Street Bullies, Shero was their general, serving behind the Flyers’ bench from 1971 to 1978. He compiled a 308-151-95 regular season record with them and a 48-35 record in the postseason. He also won his only Jack Adams Trophy with them after the 1973-74 season. After the 1977-78 season, he left them to become the head coach of the New York Rangers, a post he held for two full seasons before he stepped down midseason in 1980-81.

Prior to becoming a coach, he was a defenseman like Allen. The Rangers signed Fred Shero out of junior hockey but military service in World War II prevented his NHL debut until 1947. He played parts of three seasons with the Rangers before they traded him to the AHL’s Cleveland Barons in 1951. He finished out his playing career in the WHL and Quebec Hockey League before retiring in 1958.

Following his playing career, he coached in the minors from 1958 until 1971 when the Flyers hired him. As a coach, he was known for getting the most out of his guys without running them ragged. As mentioned above, he was a players’ coach who rarely yelled but sought to make the game fun. He was also innovative as the first coach to employ systems and study game tape of opponents.

The Rangers were the last NHL team Shero coached. He spent a season coaching in the Netherlands before he returned to be a special assistant with the Flyers in 1989. At this point in his life, he was battling stomach cancer. The Flyers inducted him into their team Hall of Fame in March 1990 and he passed away on Nov. 24 that year. He was posthumously elected to the Hockey Hall of Fame as a builder in 2013. His son, Ray, is the general manager of the New Jersey Devils.

Goalie Bernie Parent

Although Bernie Parent was not a member of the Broad Street Bullies, the Flyers wouldn’t have approached their success in the 1970s without him. His NHL career began with the Bruins who left him exposed in the 1967 Expansion Draft. The Flyers selected him and subsequently traded him to the Toronto Maple Leafs in 1971 with Rick MacLeish as part of the return. It was with the Maple Leafs that Parent honed his craft, learning from childhood hero Jacques Plante.

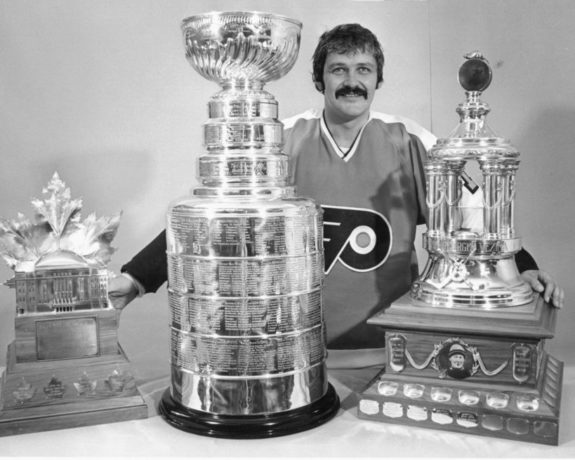

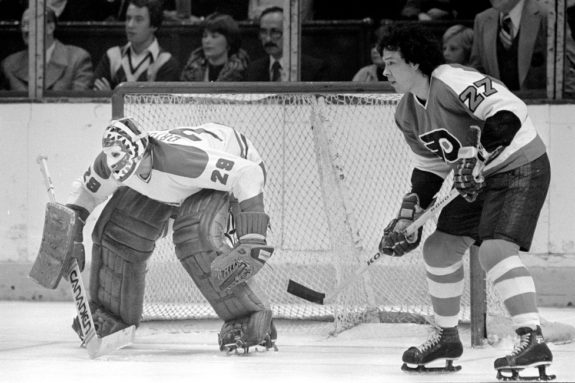

After the 1971-72 season, Parent joined the World Hockey Association and played the 1972-73 season with the Philadelphia Blazers. Afterwards, he returned to the NHL and the Maple Leafs traded his rights to the Flyers. He immediately became their starter and his 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons were phenomenal. In 141 regular season games, he had a 91-27-21 record, a .926 save percentage (SV%), 1.96 goals against average (GAA), and 24 shutouts. He won the Vezina Trophy both seasons.

He was even better in the postseason. In 1974, he finished with a 12-5 record with a .933 SV%, 2.02 GAA, and two shutouts. He allowed two or fewer goals in 11 games. In 1975, he had a 10-5 record, .924 SV%, 1.89 GAA, and four shutouts. He had nine games in which he allowed two or fewer goals. He took home the Conn Smythe Trophy both years as playoff MVP.

Neck and back injuries held him to 121 games over the next three seasons and an eye injury on Feb. 17, 1979 forced him to retire at age 34. That October the Flyers retired his number. He became Philadelphia’s goaltending coach for several seasons and mentored future Vezina Trophy winner and former team GM Ron Hextall along with Pelle Lindbergh. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1984 and was an inaugural inductee, along with Bobby Clarke, to the Flyers Hall of Fame.

Right Wing Gary Dornhoefer

Like Parent, Gary Dornhoefer began his career with the Bruins. Over three seasons with them, he had 12 goals and 24 points in 62 games. He was left exposed in the Expansion Draft and the Flyers selected him. In his first season with Philadelphia, he had 13 goals, 43 points, and 134 penalty minutes in 65 games. Between 1968-69 and 1970-71, he scored 20 or more goals twice and never accumulated more than 100 penalty minutes.

During the 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons, he scored 28 goals and 94 points and totaled 227 penalty minutes in 126 games. Between the Flyers’ 1974 and 1975 Stanley Cup runs, he totaled 10 goals, 21 points, and 76 penalty minutes in 31 games. He retired after the 1977-78 season as Philadelphia’s second-leading scorer with 202 goals and 518 points in 725 games. Additionally, he had 1,256 penalty minutes as a Flyer.

Upon his retirement, the Flyers commissioned a statue in his honor placed in front of the Spectrum to commemorate the overtime goal he scored against the North Stars in Game Five of the opening round of the 1973 Playoffs. After his playing career ended, he joined Hockey Night in Canada as a color commentator from 1978 until 1987. He returned to Philadelphia in 1992 to be in the same role and remained there through the 2005-06 season. He was a 1991 inductee of the Flyers Hall of Fame.

Defenseman Ed Van Impe

Saskatoon native Ed Van Impe played for the Buffalo Bisons of the AHL for five seasons before debuting with the Chicago Black Hawks during the 1966-67 season. As a rookie, he had eight goals and 19 points in 61 games and finished runner-up to Bobby Orr in Calder Trophy voting. After that season, Chicago exposed Van Impe in the Expansion Draft, which paved the way for him to join the Flyers.

In 1968, he became Philadelphia’s second captain in team history, a post he served until 1973. In 155 games during the 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons, he had three goals, 36 points, and 228 penalty minutes. In 34 playoff games between 1974 and 1975, he had one goal, seven points, and 68 penalty minutes. During the 1975-76 season, the Flyers dealt Van Impe to the Penguins, with whom he finished out the season but only played in 10 games the following season before retiring.

He was a traditional stay-at-home defenseman who brought little offensively. He was also not known as a strong skater but was physical and competitive. He was one of three original Flyers, alongside Dornhoefer and Joe Watson, who won both Stanley Cups. Van Impe was inducted into the Flyers Hall of Fame in 1993.

Center Bobby Clarke

The most accomplished player from the Flyers’ Cup-winning teams, Clarke made the teams well-rounded. The Flyers drafted him in the second round, 17th overall, of the 1969 Entry Draft, well below his talent level. With the Flin Flon Bombers of the Western Canada Junior Hockey League, he had 173 goals and 488 points in 162 games during his final three seasons. He slid in the draft due to a diagnosis of Type-1 diabetes as a teenager which led many to feel he’d never survive the NHL.

However, doctors believed he could play as long as he monitored his health, which was enough for the Flyers to take a chance on him. He made his NHL debut on Oct. 11, 1969 and finished fourth in Calder Trophy voting that season. Prior to the 1972-73 season, the Flyers named him captain at age 23, then the youngest captain in NHL history.

After a 100-point breakout campaign in 1972-73 when he won his first Hart Trophy, Clarke regressed slightly during the 1973-74 season with 35 goals and 87 points in 77 games. He also surpassed the 100 penalty minutes mark for the first time. During the 1974 Stanley Cup run, he added five goals, 16 points, and 42 penalty minutes in 17 games.

He rebounded for the 1974-75 season with 27 goals, 116 points, and 125 penalty minutes in 80 games. He won his second Hart Trophy at season’s end. In that year’s playoffs, he had four goals, 16 points, and 16 penalty minutes in 17 games.

He was pivotal in the 1975 Stanley Cup Final against the Bruins as he regularly went up against Phil Esposito in the faceoff dot and won a majority of draws in the series. Clarke’s impact on the game and the Flyers franchise was immense. His 89 assists in 1973-74 were a record for a center. He won a third Hart Trophy after the 1975-76 season and was an All-Star every season between 1973 and 1976. He added a Selke Trophy following the 1982-83 season.

Clarke retired relatively young at 34 after the 1983-84 season after his production fell every season between 1976-77 and 1981-82. Following his retirement, he immediately became Philadelphia’s general manager. He remained in that role until he was fired after the 1989-90 season following Stanley Cup Final appearances in 1985 and 1987. Afterwards, he served as GM of the Minnesota North Stars and Florida Panthers before returning to the Flyers for the 1994-95 season.

He moved to the team’s vice president role in 2006 and remains in that position today. Clarke is widely considered the best player in the team’s history. His number 16 was retired upon the conclusion of his playing career, he was an inaugural member of the Flyers Hall of Fame, and was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1987. He finished his career fourth all-time in assists and 11th all-time in points.

Right Wing Don Saleski

Another Saskatchewan native, Don Saleski became a Flyer after they drafted him in the sixth round of the 1969 Entry Draft. Prior to his professional career, he played for the Regina Pats, where he had 33 goals and 58 points in 40 games his final season. During the Flyers’ Cup-winning seasons, he had 25 goals, 68 points, and 238 penalty minutes in 140 regular season games.

You may also like:

- Flyers 2023-24 Player Grades: Joel Farabee

- Jakub Voracek Announces Retirement From the NHL

- 3 Most Underrated Rookies From the 2023-24 NHL Season

- Flyers 2023-24 Player Grades: Egor Zamula

- Flyers’ Ivan Fedotov Has a Lot to Prove in 2024-25

Compared to his regular season scoring average over those two seasons, his average during the 1974 Playoffs was a bit higher with two goals and nine points in 17 games. His production fell the following postseason with two goals and five points in 17 games. The Flyers traded Saleski to the Colorado Rockies during the 1978-79 season and he retired in 1980.

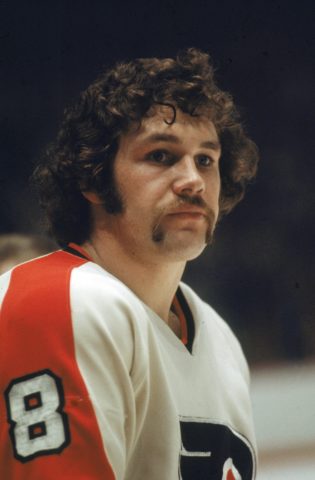

Left Wing Dave Schultz

Also a Saskatchewan native, Dave “The Hammer” Schultz was the most fearsome of the Broad Street Bullies. The Flyers drafted him in the fifth round of the 1969 Entry Draft after a productive junior career. With the Swift Current Broncos, he had 85 goals, 167 points, and 264 penalty minutes in 146 games.

He didn’t become known as an enforcer until he joined the Salem Rebels of the Eastern Hockey League once his junior career ended. In one season with the Rebels, he had 32 goals and 69 points in 67 games. However, he also had 356 penalty minutes.

In four AHL seasons following his season with Salem, he totaled 42 goals, 107 points, and 1,035 penalty minutes in 211 games. His presence in the penalty box proved to have staying power once he reached the NHL. In 1972-73, his first full NHL season, he had 259 penalty minutes to lead the league. It was his first of four times doing so. His production also dropped to nine goals and 21 points in 76 games.

Between the 1973-74 and 1974-75 seasons, he combined for 820 penalty minutes alongside 29 goals and 62 points in 149 games. His 472 penalty minutes during the 1974-75 season remain an NHL record. His penalty minutes didn’t decline once the postseason started either. In 17 games in 1974, he had 139 penalty minutes which included nine majors, six misconducts, and five games with at least 10 penalty minutes. It was a similar story in 1975 with 83 penalty minutes in 17 games. That year he had seven majors, one misconduct, and three games with 10-plus penalty minutes.

The Flyers traded Schultz to the Kings during the 1977-78 season. He also played for the Penguins and Buffalo Sabres before retiring after the 1979-80 season. He finished his career with 2,292 penalty minutes, 134 majors, one match penalty, 73 misconducts, and 25 game misconducts in 535 games, an average of over four penalty minutes per game. A regular fighter, he began taping his hands with boxing tape, a practice banned with Rule 46.15, also known as “The Schultz Rule,” which gave players a match penalty if found with tape on their hands.

Following his playing career, Schultz coached several teams in the minor leagues and was inducted into the Flyers Hall of Fame in 2009. Although arguably the most famous enforcer in league history, he has regrets for spreading a culture of violence in the game.

“I have certain regrets over my position as the hit man of hockey. I became a role model for young players such as yourself…Pretty soon there were juniors and peewees emulating Dave Schultz rather than Bobby Orr…If playing hockey means fighting, then take up golf, tennis – anything that stresses skill over simple violence.” As written by Dave Schultz in A Letter to My Son About Violence, The New York Times, Feb. 7, 1982

Left Wing Bill Barber

The Flyers drafted Bill Barber seventh overall in 1972, the highest position of any of the Broad Street Bullies. He reached the NHL in his draft year after just 11 AHL games. He finished that season with 30 goals and 64 points in 69 games and was runner-up in Calder Trophy voting. During the 1973-74 season, he had 34 goals and 69 points in 75 games and only accumulated 54 penalty minutes. He added three goals and nine points in 17 playoff games that year.

His production increased again for the 1974-75 season with 34 goals, 71 points, and 66 penalty minutes in 79 games. In the 1975 Playoffs, he had six goals and 15 points in 17 games. A reason for his uptick in performance during the 1974-75 season was his installment onto the LCB line of he, Clarke, and Reggie Leach.

Related: Bill Barber: A Flyer for Life

His production increased to a career-high the following season with 50 goals and 112 points and was an All-Star for the first time. His career ended after the 1983-84 season at 31 after he was unable to recover from knee surgery. He captained the Flyers in 1981-82 and part of 1982-83. He finished his career with 420 regular season goals, most in franchise history, and was a three-time All-Star. The Flyers retired his number in 1990, the same year he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame and one year after the Flyers inducted him into their Hall of Fame.

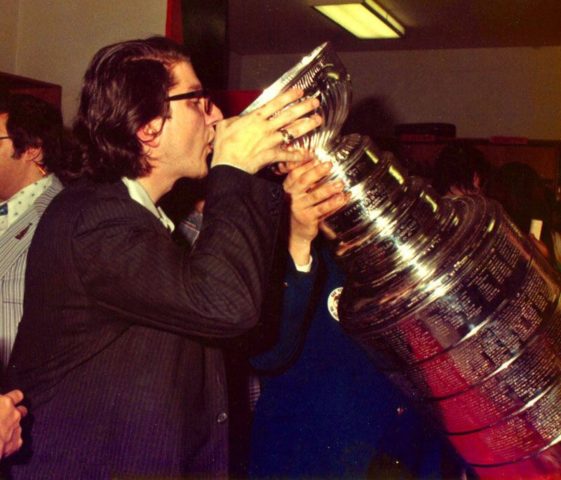

Following his playing career, he became a Flyers assistant coach for three seasons before becoming the head coach of their AHL affiliate. He returned to the Flyers for the 2000-01 and 2001-02 seasons and won the 2001 Jack Adams Award. He became the Tampa Bay Lightning director of player personnel in 2002 and won the 2004 Stanley Cup with them, his third. He returned to Philadelphia after the 2007-08 season and currently serves as a scouting consultant.

Center Rick MacLeish

The Bruins drafted MacLeish fourth overall in the 1970 Entry Draft but he never played a game with them. Instead, he started his professional career with the Oklahoma City Blazers of the Central Professional Hockey League. The Bruins traded him midseason to the Flyers in a three-way trade, part of which involved sending Parent to the Maple Leafs. MacLeish joined the Flyers afterwards and played in 26 games his rookie season.

Two seasons later, in 1972-73, he became the franchise’s first 50-goal scorer and also hit the 100-point mark for the only time in his career. He had two productive seasons between 1973 and 1975, scoring 70 goals and tallying 156 points and 92 penalty minutes in 158 regular season games. He was really good in both Stanley Cup runs, leading the postseason in points both years. In 1974, he had 13 goals and 22 points in 17 games and 11 goals and 20 points in 17 games in 1975.

MacLeish had two more productive seasons with the Flyers in 1975-76 and 1976-77, including 49 goals and 97 points in the latter. The Flyers dealt him to the Hartford Whalers during the 1981-82 campaign and he finished his career playing for the Penguins and Red Wings before retiring after the 1983-84 season. In 1990, the Flyers inducted him into their Hall of Fame. MacLeish passed away in 2016 after suffering from multiple health issues.

Right Wing Reggie Leach

From Manitoba, Reggie Leach played junior hockey for the same team as Clarke, the Flin Flon Bombers. The Bruins took him third overall in the 1970 Entry Draft and traded him to the Golden Seals midway through his sophomore season. He played two full seasons with them before the Flyers acquired him in 1974. Before joining the Flyers, he had 60 goals and 120 points in 250 regular season games. As a Flyer, he finished with 306 goals and 514 points in 606 games.

Because Leach wasn’t present for Philadelphia’s 1974 Stanley Cup and never accumulated more than 63 penalty minutes in a season, he’s not a full member of the Broad Street Bullies. Yet, his presence on the LCB Line during the 1974-75 season and beyond can’t be overlooked. He was an immediate success with the Flyers, scoring 45 goals and 78 points in 80 regular season games his first year. He was also productive during the 1975 Playoffs with eight goals and 10 points in 17 games.

But it was his performance during the 1975-76 regular season and the 1976 postseason that he is best known for. In 80 regular season games, he had 61 goals and 91 points, was a plus-72, and was named to the second All-Star team. His 61 goals led the league and remain a franchise single-season record. His postseason numbers that year were out of this world. In 16 games, he led the league with 19 goals and 24 points and won the Conn Smythe Trophy despite the Flyers losing the Stanley Cup Final to the Canadiens.

In doing so, he became the only non-goaltender to be named playoff MVP in a losing effort. Following the 1981-82 season, Leach departed Philadelphia to play one season with the Red Wings before retiring. After his playing career ended, he became a junior hockey coach and is now a scout in juniors. His son, Jamie, played on Pittsburgh’s Cup-winning teams in 1991 and 1992.

Left Wing Bob Kelly

The Flyers drafted Bob “Hound Dog” Kelly in the third round of the 1970 Entry Draft. Prior to his NHL career, he played for the Oshawa Generals when they were a member of the Ontario Hockey Association. Even in juniors he was a bit of an enforcer with 100-plus penalty minutes both seasons. In the NHL, that style of play continued with at least 100 penalty minutes in eight of his 12 seasons.

That includes the 1973-74 season when he had 130 and just missed the mark the following season with 99 penalty minutes. He didn’t provide much offensively with 15 goals and 45 points during the Stanley Cup years but he is famous for scoring the Cup-winning goal in Game Six of the 1975 Final against the Sabres.

Kelly remained a Flyer through the 1979-80 season when he was traded to the Washington Capitals. The next season he had career highs with 26 goals and 62 points and then retired partway through the 1981-82 season. Since his playing career ended, he, along with Dornhoefer and Parent serve as hockey ambassadors for the Flyers. In that capacity, he teaches children about the sport and represents the team at charity events.

The Flyers Were Really Good

As mentioned in the intro, the Flyers didn’t have the runs of the Canadiens, Islanders, and Oilers of that era. Yet, they still went to three consecutive Cup Finals and were the first expansion team to win a Stanley Cup. The 1974 and 1975 Flyers didn’t have the names that those others teams had. If you include Shero, each of the Flyers’ Cup-winning rosters had four future Hockey Hall of Famers on them. By comparison, the 1975-76 Canadiens, whom the Flyers lost to in the Stanley Cup Final, had 10 members on it.

Despite over four decades having passed since the Broad Street Bullies entertained fans at the Spectrum, the guys who made up the group will forever be immortalized in hockey lore, both due to their talent and willingness to drop the gloves. Perhaps it’s because no team since has reached the heights of the 1974 and 1975 Flyers while playing that style.

I feel confident in saying that there will not be a modern version of the Broad Street Bullies. Violence is no longer as big a part of the game as it was in previous decades. But that doesn’t dismiss what the Flyers did. As the league gets further away from the Broad Street Bullies, all we’ll have left of them will be the lore. Much like the story of Bill Barilko lives on in The Tragically Hip’s “Fifty Mission Cap,” the 1973-74 and 1974-75 Flyers teams will live on in memory as not just two of the most entertaining teams in hockey history, but also two of the greatest.